Mexico City is a city of museums

Paris, with its great tradition of art, has more museums, many of them former galleries and studio spaces. London, Moscow and Washington, D.C.—the capital cities of sprawling empires—also boast an unusual number of museums. The city in Latin America with the most museums is Mexico City, and of all the cities in the world, I would argue that Mexico City’s museums are the most charming, the most whimsical, and the most unusual.

Maybe you’d like to visit the Museo del Calzado Borceguí aka the Shoe Museum? Perhaps you’re interested in the Museo del Tiempo in Tlalpan? I’m not suggesting the people of Mexico City don’t take their museums seriously, because they do. The curation is usually excellent and in many ways more colorful and more imaginative than what you’ll find in the United States, i.e. bare white walls with track lighting. Stepping into a museum in Mexico City is always an arresting experience. Even the Museo de Cera is a trip.

Last week I wrote about visiting the Museo Templo Mayor, which you can spend all day exploring. On the last day of our visit to CDMX, we visited one of the smallest and one of the strangest museums in the city: Museo del Objeto del Objeto. That’s right: The Museum of the Object of the Object.

Situated inside a grand old house in Roma Norte, the museum is so small that it only has one exhibit at a time but it takes up all three floors of the space. The museum has a large collection of everyday objects that seek to engage the visitor in the current exhibit in interesting ways. A few years ago, we saw an exhibit about color so the objects were arranged according to the color spectrum, which was eye-catching and appealing. We learned a great deal about Rosa Mexicana, the unofficial color used to promote all things Mexico both consciously and unconsciously by architects, advertisers, and artists.

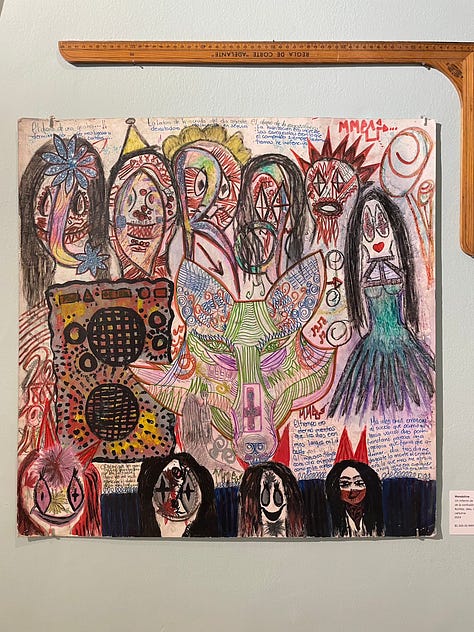

The current exhibit is much more unusual. It’s called The Rules of the Game: a collection of art by the inmates of Centro Varonil de Rehabilitación Psicosocial (CEVARESPI) and Tepepan, a women’s penitentiary. The Rules of the Game features work that is typically classified as art brut or outsider art, but I think referring to inmates as outsiders is semantically cruel. Let’s just call it what it is: the work of self-taught artists who happen to be incarcerated. It’s easily one of the strangest exhibits I’ve ever seen in a museum and I have mixed feelings about it.

First and foremost, I loved the art and I loved all the space that was given to display the art. There were probably a dozen artists featured in the exhibit and many of them were given multiple walls, some of the work took up entire rooms. Some of the artists had dozens of pieces on display. What an amazing thing, I thought, before remembering that the artists will probably never get to experience it.

I loved the repetition. I loved the patterns. I loved the commitment to certain ideas. One artist wrote his signature the same way every time: his letters meticulously printed in a circle. This artist drew happy scenes from his childhood. If it took place in a forest, there were many trees, all drawn the same way. If there were scenes on a lake, each kayak was drawn the same way. The artist had an unusual way of drawing tricycles but they were drawn the exact same way every time. This artist couldn’t stop what he was doing and search for images of tricycles on the internet, he had to rely on his memories and the tools he had available.

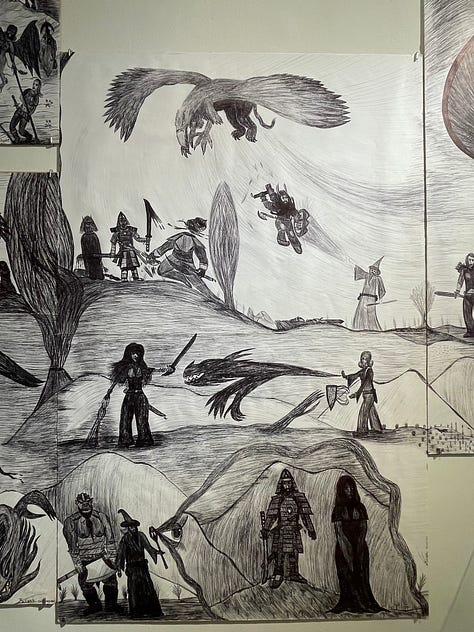

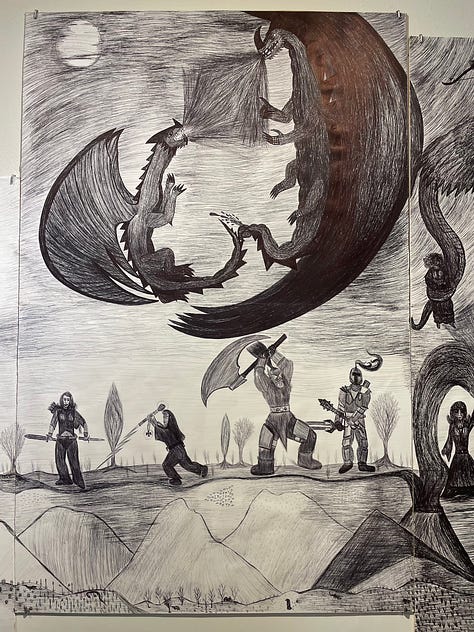

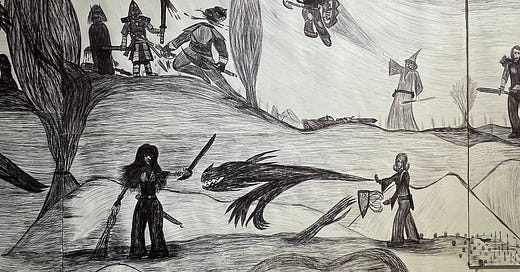

Another artist was obsessed with sword and sorcery. I don’t know if the artist was a fan of Dungeons & Dragons, Lord of the Rings novels, or Conan comic books. Maybe all of the above. Maybe none. Those are my points of reference. The artist had developed an entire pantheon of heroes, villains, creatures, and dragons. Lots and lots of dragons. Many of his characters were flat, two dimensional barbarian warriors with enormous swords, but the dragons were rendered in gorgeous, three-dimensional detail. Imagine your stoner friend from the eighth grade who drew this kind of stuff on his folders and binders was given several walls to fill up with head-chopping heroes, spell-casting wizards, and fire-breathing dragons. It was epic.

An artist at Tepepan used handmade stamps to create giant word-find puzzles. Some of the words were in English, some in Spanish, and some in a language that only the artist could interpret. Each letter was hand-stamped so that none were identical. Looking at it, the rational part of my brain demanded an answer key, wanted to know why the whole thing hadn’t been done on a computer? But the rest of my brain loved gazing up at these massive strings of letters knowing there were messages encoded inside that were beyond my comprehension. Usually it takes something sublime to shake me up like that, the majesty of nature, for example, but this artist did it with a stamp pad of ink and a big-ass sheet of paper.

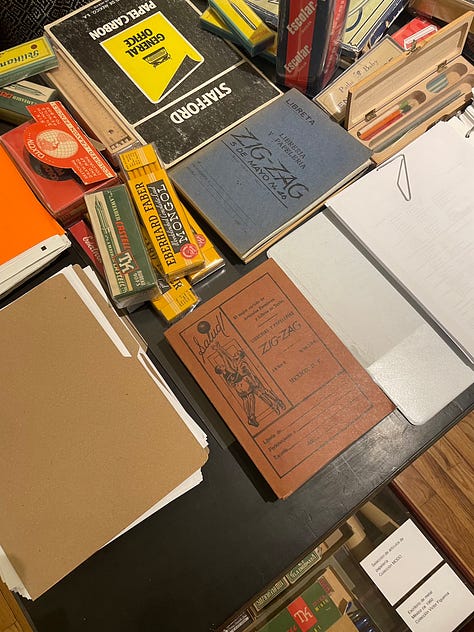

In each room, the curators augmented the art with artifacts from the museum’s collection: stacks of very old notebooks, piles of antique pencils. A photo exhibit featured a display of instant cameras of varying vintage. These objects communicated a kind of timelessness to the art. Although the artists were all contemporary, it gave the exhibition an archaic feeling, like using a sepia filter on a contemporary family photo. I understood the impulse to make use of the museum’s permanent collection, but more often than not it made the art seem stranger than it already was. Given the constraints the artists were operating under, both literal and figurative, I was suspicious of this amplification.

The aspect of the exhibit I’m most conflicted about is the text that accompanied the artwork. A few caveats. When you go to museums, do you read the text? Do you care about the placards that introduce the art and try to provide a framework for understanding it?

I do, but I rarely read all of it, because usually it’s badly written, poorly translated, or both. But this copy was well-written. Maybe something was lost in translation but it felt very 20th century in that the autonomy of the artists wasn’t considered or was outright ignored. In one instance, the text stated that the artists said there was no relation between the images in a particular piece. Then the writer went on to describe the relationship between the images in the pieces and what it meant in a very 1950s, “I’m the doctor and I know what’s best for my patients” kind of way.

I call bullshit on that. Maybe these artists lacked the language to describe what they were doing, but what if what was lacking was an opportunity to engage with the art in that way? What if the artist wasn’t consulted? What if the artist wasn’t interested in being consulted?

I could see this going either way. If I drew 100 pictures of various memories from my childhood or 100 dragons burning up villages, etc. I can see wanting to talk about what it all means forever. (I’m a novelist after all; I see narrative everywhere.) I can also see not wanting to say a fucking word about it. (Let the art speak for itself.) I’m pretty sure the last thing I’d want is some “expert” explaining what I’m doing, what I’m thinking, what the work represents. Or, worst of all, contradict me. Fuck all the way off.

There’s a place on the exhibit’s page where you can download additional information and photos, but even the introductory copy is highly suspect. Here’s a sample paragraph:

For someone deprived of their freedom, time becomes a quantifiable substance, as it defines both the future and the length of their stay in some place. Behind the walls, days transform into journeys that must be planned through endless repetitive practices, using survival strategies to combat boredom.

That is interesting and eloquent, but is it true? For each and every artist? I kind of doubt it. If I’m serving a long sentence, how many of those “days transform into journeys”? Very few, I imagine.

“Is it true?” is a question we should always have in the back of our minds when exploring museums. Is a work of art that was conceived by a famous artist but executed by assistants true? Obviously, agenda-driven museums like Christian-based creation museums are neither honest nor truthful. But aren’t all museums agenda driven? Whether guided by political forces, donor initiatives, or personal mania, someone is always putting their thumb on the scales, so to speak, especially with regards to what to include, what to leave out, and what to say about it all.

I hope I don’t sound too pessimistic about the experience because I left the Museum del Objeto del Objeto with my brain on fire and all kinds of fanciful ideas about turning my studio into a museum. What would it look like? What would I display? How many dragons do I need to draw?

For more images from "The Rules of the Game,” you can visit the museum’s Instagram page.

Books, books, books

I didn’t buy any books on this trip, but I read a few; and I read a few more since I’ve been back. Next week I’ll provide a round-up of what I’ve been reading, including a very strange book, some poetry, and lots of crime.

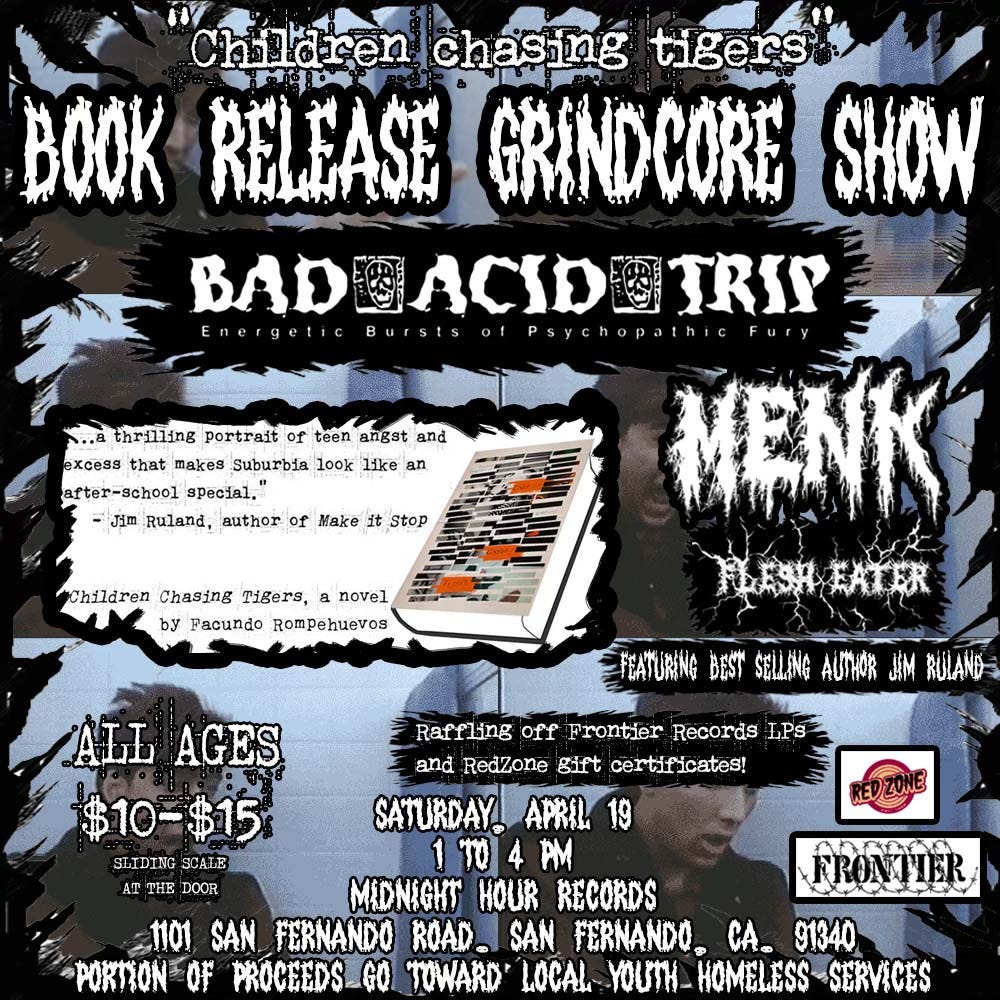

If you’re going to be in LA this weekend, I hope you’ll come see me at the book release party for Children Chasing Tigers by Facundo Rompehuevos at Midnight Hour Records at 1101 San Fernando Road in San Fernando, CA from 1pm to 4pm. There will be performances by grindcore legends Bad Acid Trip, Menk, and Flesh Eater as well as readings by Facundo and yours truly. Also, Frontier Records will be in the house. What more could you possibly want from a Saturday afternoon?

Thanks for reading! If you liked this newsletter you might also like my latest novel about healthcare vigilantes Make It Stop, or the paperback edition of Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise & Fall of SST Records, or my book with Bad Religion, or my book with Keith Morris. I have more books and zines for sale here. And if you’ve read all of those, consider checking out my latest collaboration The Witch’s Door and the anthology Eight Very Bad Nights.

Message from the Underworld comes out every Wednesday and is always available for free, but paid subscribers also get my deepest gratitude and Orca Alert! on most Sundays. It’s a weekly round-up of links about art, culture, crime, and killer whales.

If it is another individual's analysis of an artist's intent behind the work, I very rarely read it. Especially if they seem to begin to wade into the pseudo-intellectual end of the pool. I do like hearing an artist's background because it does give you some clues as to where the work is coming from. If the artist wants to tell me their thought process behind the piece, I prefer that to a full-on explanation of symbolism or message. Little clues are great. Ultimately, once a piece is out in the world, for better or worse it takes on new meaning for each viewer based on their experiences and perspectives.