These are wild time my friends. No disrespect to 2021, whose powers for fuckery are first rate, but you know what year was really wild? 1969.

I’ve been casually investigating the era through the lens of a pair of books set in that cursed year and HFS that was an incredibly weird and not-very-wonderful time to be alive.

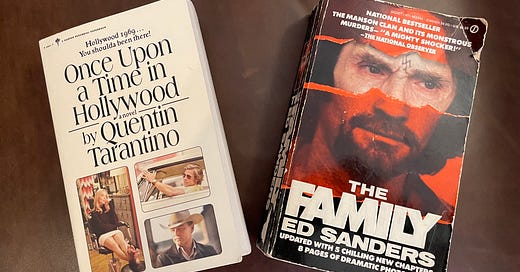

As regular readers of Message from the Underworld know, I’m a fan of Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in a Hollywood. It’s the only movie I’ve seen in the theater on multiple occasions during its initial release since I was a Star Wars-obsessed kid. So when I heard about Tarantino’s novelization of the film I snatched it up, and by the time I got through with it, I knew I needed to read Ed Sanders’s The Family next. I have so much to say about these books I’m going to make this a two-parter.

But first, a caveat: I’ve been hard at work on my SST book (Corporate Rock Sucks) and my collaboration with Evan Dando (Rumors of My Demise) but I was able to justify a deep-dive into Mansonland because of overlapping interests. For better or worse, Manson influenced the work of Raymond Pettibon, Black Flag, Lydia Lunch & Sonic Youth, and the Lemonheads. If being a writer is having homework forever, then this was an extra credit project.

Also, this post contains multiple spoilers so if you’re interested in seeing the film or reading the novel, you’d best be moving along….

OUATIH is the culmination of many of Tarantino’s interests: westerns, war movies, and old Hollywood. (Now that we’re one hundred years into this art form, old Hollywood is now a relative term, but I digress.) The novel displays several trademarks of Tarantino’s films that I want to point out before getting more specific about what I like (and dislike) about the book:

It’s very meta. It only takes a couple pages for Tarantino to start in with his “tasty beverage” bullshit and commentary on how good the coffee is. There’s Red Apple cigarettes and so on and so forth. Easter eggs galore if that’s your sort of thing.

It’s overwritten. As Tarantino’s career progressed, his scripts got wordier and wordier to the point of self-indulgence. While it was fascinating to watch a bunch of gangsters argue about the meaning of Madonna’s “Like a Virgin,” during a scene in Reservoir Dogs that does nothing to advance to plot but tells us a lot about the characters, this tendency to overwrite eventually made his work predictable, bloated, and dull. It seemed like there were always a couple of scenes in his movies that took me out of the work altogether. So I was disappointed to read several scenes that were perfect in the film—like the exchange between Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) playing the scoundrel Caleb DeCoteau and Trudi Fraser (Julia Butters) playing Mirabella Lancer—but went on and on and on in the book.

It scrambles time. Tarantino’s unconventional use of time is what made his early work so interesting. He took the conventional storylines of pulp fiction and deconstructed them in a way that felt thoroughly postmodern. The Commode Story, again from Reservoir Dogs, is a perfect example of this:

But the way Tarantino handles time in the novel is neither interesting nor innovative. Actually, it borrow from Sanders’s The Family, but more on that later. Tarantino’s narrative choices in OUATIH are bizarre. For instance, I was stunned when Tarantino related the film’s jaw-dropping, inconceivably violent conclusion to the film on page 110 of his novel, which is about a quarter of the way into the book. Furthermore, the scene isn’t narrated, but is briefly summarized in a phone conversation. I didn’t throw the book across the room, but I seriously considered abandoning it. It’s a strange choice for an author to make, and I still don’t understand it.

It’s not PC. Tarantino’s idiosyncratic language made his movies compelling and controversial in the ’90s. His films sparked necessary discussions about what you can and can’t say in a movie that felt like a direct response to the PMRC’s policing of pop culture in the late ’80s that was aimed mostly at punk and hip-hop. In his more recent films he’s ducked criticism by working within the confines of genre films set long ago, i.e. westerns, war movies, etc. But Tarantino hasn’t changed. He’s still the same person who delights in using gendered insults and ethnic slurs, which is kind of sad.

What I was looking for when I picked up OUATIH was more back story, namely about Cliff Booth, the stuntman played by Brad Pitt who steals the show and saves the day in horrific yet laconic style. There’s some irony here. I complain about Tarantino’s films being overwritten and when he knocks it out of the park with a character like Booth, a powerhouse of restraint, I want to know more. Well, Tarantino delivers and I kind of wish he hadn’t.

Tarantino fills us in on Booth’s war career, his improbable love of Japanese film, the death of his wife, his fight with Bruce Lee—all of it. Even Brandy, the pit bull gets a back story. The problem with this is Tarantino turns a character who is tantalizingly inscrutable into a cartoon. Booth didn’t just fight in WWII, he had the most confirmed kills of any solider in the Pacific theater ever. He’s not someone who disguises his deadliness with a laid-back demeanor, but the baddest, motherfucker on the planet. Okay.

One of the tantalizing aspects of Booth’s story in the film is that he is believed to have gotten away with killing his wife. In the film, Booth’s wife Billie drunkenly berates him. Booth dressed for an afternoon of underwater spearfishing, says nothing, and the scene cuts away. We’re told that he murdered his wife but we don’t see it. Was it an accident? A moment of madness? Or a calculated act? The ambiguity is essential to how we view Cliff. We need to know that he’s capable of murdering his wife in cold blood, but also that it’s possible that it was an accident and he carries the burden of that with him.

Well, the book tramples all over that. He kills her with a shark gun, whatever that is, that literally cuts her in half. In the book, he holds his wife together while she dies in his arms and the two even make peace with each other despite the horrific violence he has visited upon her. Give me a break. Can you imagine if Tarantino had tried to film that scene? It’s not just the violence that’s troubling, but that the victim releases the perpetrator from emotional bondage by forgiving him. I liked Mr. Booth a lot less after that. This cuts to the heart of my problem with Tarantino’s films: they aren’t stories, but artfully constructed set pieces that allow the maximum amount of carnage that he feels he can get away with.

Even Brandy’s backstory is over the top. Brandy was a champion on the dog fighting circuit, a ruthless killing machine who was capable of inflicting unspeakable carnage on her foes. When Brandy get hurt and her owner reveals that he is prepared to put her back in the ring and bet against her, Booth kills him and retires Brandy. This is what passes for heartwarming in Tarantino’s universe. Again, Brandy isn’t just a well-trained fighting machine, she’s the baddest motherfucker on the circuit. (I do like that she gets star billing on the spine of the novel.)

What makes OUATIH the movie so good is its subtlety and restraint, but neither of these characteristics are on display in the book. The book is a depository for Tarantino’s violent fantasies about maleness and masculinity that feels phonier then a western movie set.

Was there anything I did like about the book? Honestly, not much. I liked the book’s mass market paperback design and price point. While I respected Tarantino’s commitment to exploring every facet of Dalton’s career, going over every role and who he’d worked with and then integrating it into real Hollywood history in a way that makes it hard to tell where the fiction ends and history takes hold, I didn’t find it all that compelling. It felt like the book was a vehicle for Tarantino to spout off about television westerns, Akira Kurosawa’s films, and so on. It’s more like a long-winded director’s cut than a novelization.

For instance, Booth offers his top five Kurosawa movies. So you’re telling me a guy who fought in the Pacific and killed over a hundred Japanese soldiers has a secret passion for Kurosawa films? No he doesn’t.

What I did find fascinating was Tarantino’s deep dive into the script of the Lancer pilot that Rick Dalton is guest-starring on. In the film, we see a few scenes, like this one:

(One thing that has always bothered me about this scene: why is Johnny Madrid standing in front of his hors? Does he not care if his horse gets hit with a stray bullet?)

In the novel, Tarantino explores the story-within-the-story, animating the Lancer plot in the pilot, giving the players their own backstory, and throwing them into a saga. It’s like a mini Louie Lamour novelette packed into the novel. Tarantino doesn’t do this for the sake of doing it. This fictional storyline is the thread that connects Dalton and Fraser in a way that is far more substantial than what we see in the film.

The novel also features the Manson family shenanigans at Spahn Movie Ranch, and there’s a quite a bit more to it than what we see in the film. This is what led me to read The Family to determine what Tarantino had made up and what he’d lifted from Manson lore, and what I found is pretty interesting.

But I’ll tackle that in Maniacs in Hollywood Maniacs Part II in next week’s edition of Message from the Underworld.

San Diego Show Alert

Aside from a karaoke party, I haven’t been to a live music event in a year and a half. I was looking forward to a couple SoCal shows this weekend, but with the rise of the Delta variant I’m not going to risk it. However, one of these shows has been moved to an outdoor setting, so I’m going to give it a shot.

This Sunday afternoon I’ll be at Green Flash Brewery to see Come Closer, Slow Death, Worriers, and Mickey Erg. An all ages Sunday matinee? That is definitely my speed.

Please note, you must be vaccinated to attend and be sure to mask up. All the details are in this rad flyer that Bill Pinkle designed.