[THIS EDITION CONTAINS SPOILERS. IF YOU HAVE ANY DESIRE TO SEE ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD, SCROLL DOWN TO THE LIT PICS.]

I thought I was done with Quentin Tarantino.

The gratuitous violence, the overwritten dialogue, the self-indulgent scenes had worn me down. His movies had lost the capacity to shock or surprise. I had the feeling he was making films simply to satisfy his inner fan boy, because no one could keep up with all the references and allusions (and outright thefts) in his filmmaking.

I loved Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994) because of their debt to the noir novels by David Goodis, Dashiell Hammett, and Jim Thompson I poured over in between shifts at the coffee shop, which just so happened to be located on the border of North Hollywood of Toluca Lake, where I worked from the summer of ‘92 to the spring of ‘93. Those movies were a reflection of my weird tastes and reflected both my immediate surroundings and the landscape of my imagination. But with each subsequent film the magic seemed more and more remote. It was Django Unchained (2012) that finally kicked me off the Tarantino bandwagon.

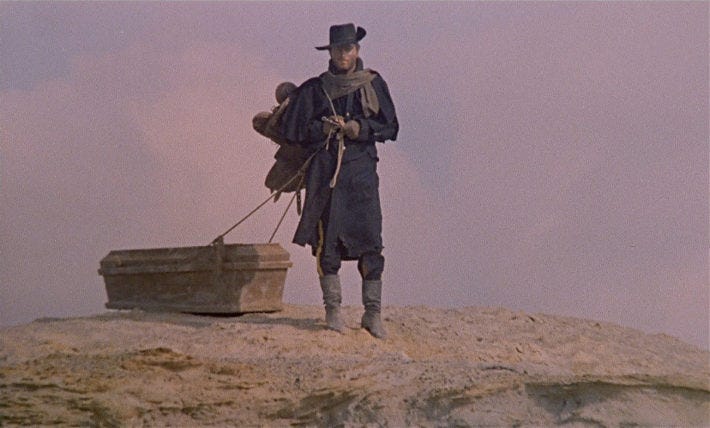

I had high hopes. Like Tarantino I love spaghetti westerns and for a brief period of my life I was obsessive about them. Like Tarantino I prefer Sergio Corbucci’s films to Sergio Leone’s. And like Tarantino I love Franco Nero’s coffin-dragging performance as Django (1966).

(Alex Cox, another outstanding filmmaker, loves spaghetti westerns so much he wrote a book about them.)

But Django Unchained is a baggy, bloated parody of a spaghetti western and his decision to make the bad guys white slavers, like Inglorious Basterds (2009) before it, felt like an excuse to rack up the body count for his over-the-top fight sequences. I saw the film over the holiday break, not long after the murders at Sandy Hook, and for me the endless shootout scene where bodies are used as shields marked the point where the times had officially left Tarantino behind.

I didn’t even bother going to see The Hateful Eight (2015) As far as I was concerned, Tarantino had run out of ideas.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood proved me wrong. I think it’s his best film and close to a masterpiece. A lot of really smart things have been written about it, but what I find so exciting is that it’s something I’ve never seen before in a movie. It’s somewhere between a fable and a fairy tale, an alternate reality where the line between what’s “real” and what’s not is blurred and those who are the best at blurring those lines (aka actors) cross over from one world into the next and then back again.

It’s a counterfactual film that doesn’t just pose the question, “What if Sharon Tate hadn’t been murdered by the Manson Family?” it forces us to inhabit the world of two actors: one “real” (Sharon Tate played by Margot Robbie) and one not (Rick Dalton played by Leonardo DiCaprio) and one stuntman (Cliff Booth played by Brad Pitt). OUATIH explores how they fit together in this alternate universe where Sharon lives, Bruce Lee is more of a dancer than a fighter, and the Manson Family is prevented from making a dent on the dark side of pop culture.

The film unfolds like a novel. But if it were a novel, on what shelf would you put it? My friend Josh Mohr contends OUATIH doesn’t belong to a genre and I agree. It’s simply the story of three days with three Hollywood professionals. When a character in the movie has to move from one place in L.A. to another, we go with them, see what they see, hear what they hear – sights and sounds that sync up with Tarantino’s own childhood memories.

It’s easy to say that not a lot happens during these scenes, but that misses the point. One of the most crucial scenes in the movie occurs when Rick sends Cliff to his house to fix his TV antenna. Up on the roof, Cliff remembers the day he was kicked off the set for fighting with Bruce Lee in a “friendly” sparring match, a match Cliff was on the verge of winning before he was dismissed. During this scene, Cliff has a flashback within the flashback, a brief scene in a boat that shows him being harangued by a woman, presumably the wife he got away with killing. Not only is the flashback inside a flashback a Thomas Pynchon-level narrative leap, the fact that we never see the murder or the corpse is exactly the kind of restraint that has been sorely lacking in Tarantino’s films for the last decade.

This introduces a level of ambiguity to Cliff’s character that shrouds him in mystery usually reserved for movie stars, not the grunts who “carry the load.” A stuntman gets the job done or he doesn’t get to be a stuntman anymore. There’s no ambiguity about it. After the flashback, still up on the roof, taking in a bird’s eye view of the neighborhood that in our timeline Manson would make infamous, Cliff can only shrug in resignation as if to say, “Yep, that one’s on me.”

Cliff makes the movie work. Without Cliff carrying the load, we don’t get that magnificent ending, but every scene he’s in anticipates it. Whereas Rick plays a number of roles, some better than others, and takes pride in his craft, Cliff has a code. It’s a complex code, one that puts an extremely high value on loyalty and doesn’t preclude violence toward women, but a code nonetheless.

Early in the film, when Rick realizes his career as a leading man is on the wane (unless he takes matters into his own hands, something he seems unwilling to do) Cliff tells him not to “cry in front of the Mexicans.” This seems superior and casually racist, but isn’t. Cliff understands and even embraces the machismo of the Mexican workingman. He knows these men will lose respect for Rick if they see him crying in public. And that he cannot allow. He may agree with the valets that it’s foolish to get upset about a problem that is easily fixable, but his loyalty is to Rick Dalton first, last, and always.

Cliff’s role is described at the outset of the movie--he carries the load—but Rick gets all the credit. Cliff is “a goddam war hero” but the only one who acknowledges that is Rick, who gets lauded for his performance as a war hero in The Fourteen Fists of McClusky throughout the film. At the end, Cliff saves the day, but Rick gets all the credit, and possibly saves his career, by delivering the coup de grace with the flamethrower. While Cliff takes a ride in the back of the ambulance after getting stabbed in the hip, the barrier to the next phase of Rick’s career, one that possibly involves Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski, swings open.

As much as I love Cliff’s character, my favorite scenes in the movie are Rick Dalton’s two scenes with Trudi Lancer, played by Julia Butters. Rick is playing the role of a heavy, or at least he thinks he is, but Trudi inspires him to care. He’s having a bad day and all too ready to wade into a boozy pool of self-pity, but as a result of his interaction with Trudi, he remembers who he is: an artist. An artist is many things but an artist almost never succeeds by showing up hungover and mailing it in. Trudi reminds Dalton that art is never easy. Whether you’re riding a good streak or a bad one, on your way up or on your way out, the work that makes art possible never becomes any less demanding. Dalton can nurse his resentment and go through the motions, or he can do the job he was hired to do in a way that no one else can do it, because he’s Rick fucking Dalton.

(Apparently a third scene between Rick Dalton and Trudi Lancer was filmed, but was cut. I am very curious to see that scene.)

For me, watching Rick get through his tongue twister lines is every bit as thrilling as watching Rocky pick himself up off the canvas in a heavyweight title fight. The stakes are that high.

Is Tarantino Rick? A talented artist with a hard-to-define career somewhere near the top of his long slide into obscurity? I don’t know and I don’t care. I do know that for once Tarantino marshals his tendency to overwrite in the service of the film by putting deliciously corny dialog in the mouths of TV outlaws.

Tarantino knows what he’s doing. No one has ever questioned that. His erudition is only outpaced by his passion, or perhaps the two go together like hand in glove, but OUATIH is so entertaining because it antagonizes the viewers’ expectations, not by going over the top but by showing restraint, by being self-aware, and by following Cliff’s code to its shocking conclusion.

And it is shocking—but probably shouldn’t have been. This is what Tarantino has been doing for years. He picks the most despicable bad guys so he can inflict gruesome violence on them. Nazis. White slavers. Why should the Manson Family be treated any differently? I should have seen that ending coming, but I didn’t.

I saw Quentin Tarantino’s OUATIH in the theater three times this year, and would go see it again in a heartbeat. After reading Tarantino’s long interview with Kim Morgan, I had to go see it again. Ditto after reading Priscilla Page’s piece. Perhaps this will inspire you to see it again in the theater now that awards season is upon us. Maybe we can all go see it together. All I know is OUATIH gave me more pleasure than any other movie I watched this year.

I like OUATIH so much I even made fan art. I made a handful of not very good prints of Quentin Tarantino’s portrait. If you’re a subscriber and you’d like one, drop me a line with your address and I’ll send one to the first half-dozen or so people that respond. They’re approximately 6” by 8”. Some are black. Some are red. Some are black and red. But none are good. I’m not being humble. They’re just not that great. But if you love OUATIH as much as I do, then maybe you’ll appreciate it. Maybe.

Sympathy for the Detective

Last week I told you I was going to read The Sympathizers by Viet Thanh Nguyen. I lied. I went to L.A. and Todd Taylor lent me a copy of Claire DeWitt and the Bohemian Highway by Sara Gran. It’s the second in the series of novels that features Claire DeWitt, the world’s greatest detective, and the most exciting detective series I’ve read since Elizabeth Hand’s Cass Neary novels. So I scuttled my plans and dove in and I don’t regret it one bit. I’m saving the third novel in the series, Infinite Blacktop, for the last novel I read in 2019, so I’ll have more to say about Claire DeWitt in the coming weeks.

Lit Pics for 12/12-12/18

With the holidays approaching, there aren’t a ton of literary events going on but these are some of my recommendations in Southern California.

Thursday December 12 at 7pm (SD)

The Catapult Book Club will discuss Samantha Hunt’s novel The Seas. (Hot tip: Book club selections are 20% off the month before the meeting). This event is free and open to the public.

Friday December 13 at 6pm (SD)

Perhaps may favorite thing about the English is their tradition of infusing the holidays with tales of supernatural trauma. Verbatim Books is hosting an evening of Victorian ghost stories with Chris Ernest Nelson. Free and open to the public.

Saturday December 14 at 4pm (LA)

Indie Small Press Day at Book Soup will feature publishers and authors from Angel City Press, Unnamed Press, and Red Hen Press. Refreshments will be served.

PLAN B (SD)

Mysterious Galaxy presents YA phenom Tony Adeyemi, author of Children of Virtue & Vengeance, in conversation with Adalyn Grace at the San Diego Central Library at 2pm. This is a ticketed event so plan accordingly.

Sunday December 15 at 2pm (SD)

Award-winning writer and television producer Kevin Shinick will sign Star Wars: Force Collector at Mysterious Galaxy.

Monday December 16 at 7:30pm (LA)

Tom Lutz, founder and editor-in-chief of Los Angeles Review of Books, will discuss his debut novel, Born Slippy, with novelist Steph Cha, author of Your House Will Pay and the Juniper Song detective series.

Tuesday December 17 at 7pm (LA)

Stories Books and Café will host a Black and Pink LA Holiday Card Party where you can send a holiday message to incarcerated queer and trans folks.

Wednesday December 18

You’ve got one week before X-mas. Remember, many independent bookstores will ship books to your friends and family. Resist Amazon and shop indie this holiday season.

Thanks for reading Message from the Underworld.