When I was in the Navy I didn’t watch much TV, but I made up for it by taking lots of LSD. I’m kind of kidding, but also kind of not.

The first time I dropped acid I was on duty. The ship was in port and my job was to make sure no one put any flammable material into a dumpster on the pier. I watched that dumpster all right, and when the acid kicked in the splotches of rust started moving in slow motion, like a mouth, a mouth with something to say…

The dumpster didn’t talk to me that night—thank goodness—but I was so transfixed by the face on the side of the dumpster that I didn’t notice someone dumping several cans of paint in it. I got dressed down by an officer the following morning, which struck me as very funny even though I knew this was not a funny situation. In fact, it was quite perilous because, as you can imagine, I was always in some kind of trouble.

Standing there on the pier at the dawn of a gray San Diego day while getting chewed out by an officer, I could feel my brain fragmenting. I was there answering the officer’s questions (“Yes, sir. No, sir.), but also not there. There was the version of me that avoided this kind of trouble and the version that sought it out. There was the version that pantomimed the role of a contrite sailor and the version that wanted to know what the dumpster had to say. It’s a miracle I didn’t end up on the psych ward.

I kept taking acid when I got to college. I found the nightlife in my college town dull and predictable. Everyone went to the same bars depending on the day of the week. My roommates watched the same shows on TV every night before going out. This frustrated me. Didn’t they understand how much freedom they had? Didn’t they know there was a great big world to explore?

I was older than my peers and had been around the world. Pounding beers during Wheel of Fortune wasn’t going to cut it.

Taking acid was a way to make things more interesting, which was kind of a catch-22. Did interesting things happen to me because I was making them happen or was I paying closer attention to the world around me?

Answer: both at once. Both answers weren’t just true, they were simultaneously true.

I liked the way my brain worked on LSD. I liked the clarity that it provided. A few years later, in a critical theory class, while reading about Longinus’s barriers to the sublime, I immediately thought of LSD, the way it stripped away pretense. The brain on acid mowed those barriers down.

There were certain types of music that was more fun to listen to while on acid, like Butthole Surfers and Sonic Youth, and certain types of movies that were more fun to watch while on acid, like David Lynch’s movies, namely Eraserhead, Blue Velvet, and Wild at Heart, and I gravitated toward them. (But not Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. For the love of god don’t watch Fire Walk with Me on LSD.)

Lynch’s films were full of images, dialog, moments that were superfluous to the plot but I recognized as “things that happen while on LSD,” things that don’t make sense on the surface, but feel like they belong or are true to the character or introduce an entirely new perspective. On acid, you can’t dial up your hallucinations and give the dumpster on the pier a French accent, but in movies you can and Lynch exploited that freedom like no one else.

Like in Blue Velvet, when Jeffrey comes back from college and discovers an ear that he turns in at the police station. He wants to know more about it, and stops by the detective’s house to see how the case is going. The detective brushes him off, but Jeffrey questions the detective’s daughter during a walk around the neighborhood. And this happens:

One second you’re pointing out a house where someone you knew used to live and the next thing you know you’re doing the chicken walk.

“That’s interesting!” Sandy says.

There’s a whole Reddit thread devoted to unpacking what it might mean even though it doesn’t “mean” anything. That’s not how Lynch’ films operate. That’s not how dreams work. That kind of discussion isn’t remotely interesting—never mind what Sandy says.

We reveal things about ourselves at certain times and in certain places that we normally keep locked up tight. We share things with strangers in airports because we’ll never see them again. We talk about ourselves during long car rides to fill the time. In the Navy, we’d tell each other stories about our friends, our girlfriends, our lives back home so that someone would know something about who we were before we put on the uniform.

In Lynch’s film Wild at Heart Sailor and Lula tell each other stories in the car and late night in the motel room between cigarettes and sex. The scenes Lynch conjures up from these stories are the stuff of nightmares.

That’s so weird, you’re probably thinking. Crispin Glover’s over-the-top performance in stark contrast to Sailor’s dreamy eyes and Lula’s sweet Southern accent.

Most of that scene exists on the page of Barry Gifford’s novel Wild at Heart. Lula is telling Sailor about her cousin. The lunch scene, the black gloves, the mysterious disappearance are all there. The Christmas angle is new as are the cockroaches, but Gifford, Lynch, Glover, and who knows how many others collaborated to create something that gets to the essence of poor Dale’s dilemma, the lack of barriers between his life and madness.

Sometimes we need those barriers. Sometimes we need them taken down.

In the novel, Lula frames the story around the first time she got pregnant at the age of 15. Dale was the father and the story of how her mother took her to Florida for an abortion is even more harrowing. All in the span of about five pages.

LSD, Lynch’s movies, Gifford’s books—all gateways to places I couldn’t reach on my own, but they got me there. I think the danger of LSD is mistaking the clarity of the experience for The Truth. Pairing art with acid, especially subversive art, makes it clear there are many truths. This isn’t a radical idea when we think about what individuals bring to art. You and I are going to have a different experience of a work of art—what thrills me might leave you cold and vice versa.

The radical idea that Lynch manifested is the artist as a multiplier of meaning who presents many perspectives of not just narrative, but of reality itself. He uses familiar frameworks—a detective story, a road movie, a missing girl—but that’s all they are. Breadcrumbs to a place deeper in the woods where the normal rules don’t apply. And why should they? We aren’t watching Sailor and Lula, but actors pretending to be characters who exist only in the imagination. Writer, filmmaker, reader, viewer, we all participate in the conjuring.

Wild at Heart is probably the most accessible of all Lynch’s films. The title of both the book and the move signals romance, rebellion, and freedom. Of course Lula is going to run off with Sailor, a convicted murderer, because she’s full of passion, their wild love can’t be contained, all that palaver.

You could use Lynch’s film to make a music video for a pop song called “Wild at Heart” that’s full of sweetness and light. Or, you could make a version that’s much, much darker. Lynch offers both. He rejects the Aristo-Boolean logic that has guided civilization for thousands of year. We are neither good nor bad but both-at-once. That’s what makes life so unpredictable, so confounding, so beautiful.

The line the title comes from is much darker. “The world is really wild at heart and weird on top,” says Lula in the novel. She’s talking about the unrelenting strangeness of the world, the savagery at the center of things, chaos.

A lot of people never get past the stuff that’s weird on top, both in fiction and in real life. “That’s so surreal,” they say of Lynch’s films or anything outside their world view. That’s the barrier the seeker must overcome, to go beyond, because what you find there is yourself.

I don’t take acid anymore. I’m not the least bit curious about micro-dosing. Allen Ginsberg famously said, “It’s not the trip, but what you do with it.” The work is looking out for the barriers that others put on us and those we put on ourselves that prevent us from experiencing the sublime beauty of the world as only we can see it.

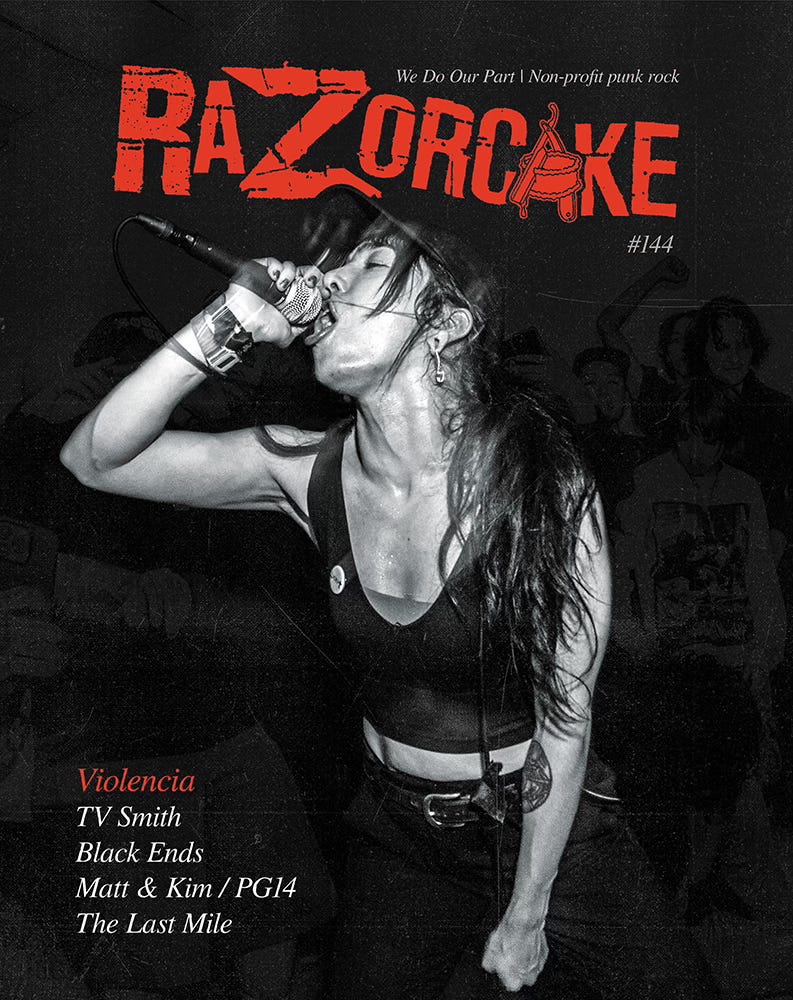

Razorcake #144

The new issue of Razorcake is out and it’s a stunner. I wrote about the Dead Boys debacle. Do your part, and subscribe.

If you liked this newsletter you might also like my latest novel Make It Stop, or the paperback edition of Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise & Fall of SST Records, or my book with Bad Religion, or my book with Keith Morris. I have more books and zines for sale here. And if you’ve read all of those, consider checking out my latest collaboration The Witch’s Door and the anthology Eight Very Bad Nights.

Message from the Underworld comes out every Wednesday and is always available for free, but paid subscribers also get my deepest gratitude and Orca Alert! on most Sundays. It’s a weekly round-up of links about art, culture, crime, and killer whales.

Good stuff amigo

Enjoyed this one, bud!