And now for something completely different…

Since I started writing about boxing and posting pictures from the gym where I train, I’ve heard from a lot of readers, writers, artists, and musicians who share my passion for the sweet science. One of those people was Peter Finestone who was Bad Religion’s drummer during the late ’80s and early ‘90s, most notably during the run that produced Suffer, No Control, and Against the Grain. Peter shared some of his stories with me recently, but they were too good not to share. So I reached out to him about doing an interview and here we are.

Before we get started, I want to thank you for reading Message from the Underworld, especially those of you who are new or recently renewed your subscription. Please feel free to leave a comment or reply directly to the email. I love hearing from you and try to respond to every message. If you like The Sweet Spot and would like to see more of these, please let me know. Or, if you know a creative person who would be a could subject for this interview series, please let me know. Now, I want you to shake hands and when the bell rings come out fighting…

Jim Ruland: Let’s begin with your boxing journey. How did it start for you?

Peter Finestone: Thank you for that question, Jim. I don't get a chance to really share this a lot. Throughout my life, beginning when I was young, boxing has always been a response to some depression or sadness I was going through. It started when I was a young kid. I think I was 12. I grew up in Northridge in the San Fernando Valley, which was a pretty conservative town. I went to a public school and when I was younger, I was picked on mercilessly because I had a stammer. Like every goddamn day. It got to a point where my mom and dad really had no answer. “Well, do you want to move schools?” I didn’t see the point. If you have this issue, it doesn't matter if you move.

They’re just going to tease you at the next school.

Right, so we had a neighbor who was my dad's friend. He was a raging alcoholic, Mr. Humphrey, but for some weird reason, I was able to connect with him. I remember I told him, “I don't want to go to school because every day is a battle.” I was picked on every day. My mom and dad didn't have an answer. The teachers didn't care. I was so tired of it. Mr. Humphrey took me to this boxing gym called Left Hook. It wasn’t far from where I lived. So I walked through the doors of Left Hook and there was this old school boxing coach. Within six weeks, I learned the basic fundamentals of boxing. I went back to school and I wasted no time. The first dude who came at me, I put him down. I think he was stunned. His name was George and he was my main tormentor. It's funny because we became friends, not real good friends, but afterwards he wanted to become my friend.

He didn't want that smoke.

Yeah, that was the start of my understanding that boxing was the answer to what I was going through in my life, not just because it provided me with self-defense, but it also provided me with mental toughness and a strategy to help me navigate problems in my life. The most important thing is I felt empowered for the first time. The ability to have some kind of answer when I had to protect myself, and to get that at that age, was a real breakthrough for me, emotionally and physically.

You were probably already mentally tough from dealing with the stammer without even really knowing it.

Yeah, I never thought about it like that. It just sucked. It's not like now. I have kids, and there's a lot more help, and there's a lot more public awareness. If a kid has something going on, don't give the kid a hard time. There's more anti-bullying messaging now.

More awareness of learning differences.

Exactly. Back then, it was just merciless. Now, kids have some kind of help to prevent classrooms from turning into Lord of the Flies.

So let me ask you, after you left Bad Religion, you had an opportunity to get involved in the other side of boxing.

I was 28. I had made, in retrospect, a rash decision to leave Bad Religion because I was also playing with another band that had gotten signed, and for some reason being the drummer of BR wasn’t enough. I always wanted more. I had a lot of fear of not being good enough. Always wondering if Brett was going to be like, “We need to replace you.” There was always a tension, at least in my mind, that I was on the precipice of being let go. So I felt this was my out. I can be in this other band where I play drums and help write songs. So that band recorded an album and Electra never put it out. They dropped us, which was brutal. So in a span of six months, I had left the band that helped define who I was, and the other band I had left them for was done, and the girl who I loved and shared an apartment with for four years packed up and moved in with another guy. So I had this trifecta of loss.

That sounds like you had a lot on your plate.

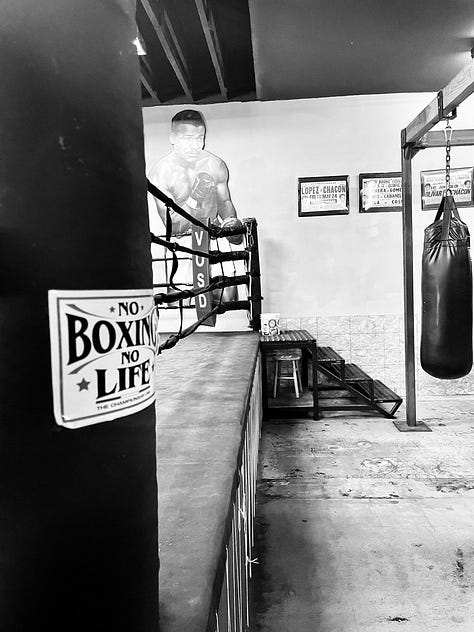

I was in a bad place. I was severely depressed, and it was hard just to wake up in the morning, because I had lost everything so quickly. And the worst part about it, Jim, was that I blamed myself. You can't predict what's gonna go down, but I knew I had made a poor choice. So I would go on these runs. The only way to deter the depression taking over was by working out. One night, I went on an extra-long run because I didn't want to go back to my little one-room place in West Hollywood and be miserable. So I stopped to take a break at Fairfax and Fifth and I look up and there's a sign: Fifth Street Boxing. This guy came out and introduced himself. His name was Phil Paolina, and he had a super thick New Jersey accent. He said, “I'm closed, but why don't you come in?” This gym was maybe 900 feet square and it had heavy bags, speed bags, and he had covered every inch of the wall with old posters of all the great fighters. It was like a boxing heaven.

It's funny, Pete, because I went to a gym this morning to train and it's just like you're describing it. There's history and an old school aesthetic. There's just nothing else like it.

There really isn’t. Long story short, Phil said, “Well, put on the gloves.” I'm like, “Dude, I haven't hit in blah, blah.” He said, “Stop making excuses.”

That's the mentality right there.

He was cranking some ’90s hip-hop, I think it was Public Enemy, and we started to work out. We went through the punches, the counter-punches, the balance, the whole nine yards. For one hour, I forgot all about my fucking self-pity and about how I had fucked up my life so badly. For one hour, there was a respite from all that fucking chaos. The workout, combined with the focus and concentration, helped me reduce the stress and the anxiety I was feeling. It was also cathartic.

How did you come to get involved in the coaching aspect of it?

So fast forward, I went to that gym every goddamn day. I trained three hours a day. Every day. I would do road work in the morning, up at six, I trained like I was a fighter, right? I was there so much Phil gave me the goddamn keys. And then one day, I was started to see some money come in from the band, so I said, “You know what we need in here, Phil? We need a 12-foot ring.” And he's like, “I can't pay for that.” I told him, “What if I paid for the ring, and we became partners?”

So you bought a boxing ring with your Bad Religion royalties?

Yep, it was probably like $3,000 or something. A pro ring: canvas, buckles, side wings, ropes. Everything pro, because Johnny Flores did it and he made all the rings for all the fights. So I started to learn how to train people, how to hold the mitts, how to focus on their balance, on their combos, on their counters. And it became my passion. After a year, we moved into a space over on Wilshire that was five times as big as the space that we had, which I thought was a mistake, and I bought two more rings: an 18-foot ring and a 22-foot ring. That started to attract pro fighters.

Let's back up a little bit. Who were some of the celebrities you worked with?

I worked with John Schaech. He was the star of That Thing You Do with Tom Hanks and we also trained Ari Emanuel. He was one of the biggest agents in Hollywood at the time and he was insane. Mickey Rourke would come in. I worked with Greg Graffin one time when he was in town for a show, which was kind of bittersweet. I also trained Brett Gurewitz and I had Johnny Flores build Brett a ring in his backyard. I kid you not.

Give me a rundown of their strengths in the ring.

Greg is really athletic, I think he would have been great if he stayed at it, but we just did the one day. Brett, one thing I have to give credit to Brett for, he was determined. I mean, he wanted to train every goddamn day. So he had a real good work ethic, which I think you know about him. That goes to everything he does. Once Brett learned how to use his core and his feet and his weight, he had a really good right hand. I always wanted to get Brett to a place where he could come to a gym and spar just to see how he would do against an actual opponent. Anyone I trained, I tried to get them to the point where they could spar. Maybe not against a pro or whatever, but just to get them past their fears, because that's what sparring is for a lot of people. They're scared to death, right? You get them into a ring with somebody who knows what they're doing and get through that fear of actually hitting and being hit.

What changed for you?

I started to get in the ring and spar with a lot of these pros. I could box, but I was scared out of my mind. They would go maybe 50 percent. These guys are pros. With one shot they could put me out. That really helped me with my self-esteem. Helped me feel like, “If I can get through these three rounds with this pro, then I can get through whatever I have going on in my life.” That might sound cheesy, but that's how I looked at it.

I don’t think I’m there yet, but I totally get it.

So we trained the pros, and some of our pros started to have fights. So I got to work corners for these local fighters. Nobody you would know or you would have heard of, but it was intense. These were actual fights and sometimes I would drive the fighters home afterwards. Most of them lived in South Central. So I would drive them back to their place, and a lot of them lived in projects. They were fighting because this was their way out. It gave me a new perspective on how hard it is. Sometimes my life was hard but compared to what these guys were dealing with? No comparison.

It’s one thing to train, but another to be there when your guys are in the ring.

It was a heady time. But after three years, I got tired of working with Phil because part of our agreement was after a certain amount of time, I would to start to make some cash too, and it wasn’t happening. I was getting hosed. It hit me: I'm at the stage where I could train people and make money, but not here, because every cent I make goes to him. Long story short, the day Kurt Cobain died, I said, “Phil, I'm done. I need to leave. You can pay me for one of the rings, and we'll call it a day.” He lost his fucking mind. People had to come get in between us.

It wasn’t meant to be.

But I saved the best story for last. About a year after I left Phil, he calls me up. “Peter, get down here.” I'm like, “Phil, what do you want? I’m not just going to run down to the gym.” He said, “I got Bob Dylan here, and I need you to get in the ring with him and let him throw punches at you.” I'm like, “Okay, no problem.” So I get down to the gym and I see Bobby D putting on the headgear and Phil goes, “Bob, this is your sparring partner.” And Bob's like, “Okay.”

So I get in the ring with Bob Dylan, and proceed to spend the next four rounds moving around the ring with him. He’s throwing jabs, maybe a hook. I'm pretty much just letting him throw at me. Occasionally I'll snap a jab at him but I’m thinking, “This is surreal. This is so weird.” The best part was the last round/ Bob wanted to quit but Phil wouldn’t let him. “One more round, Bob!” There was all this snot coming out of Bob's nose, and his mouthpiece was half in, half out of his mouth. This is ’94 so there are no phones. No one’s taking photos. No one even knows who he is. We did that probably twice. The second time, when we were done, I got to talk to him a little bit. He had just gotten done with his tour with the Grateful Dead and so I asked him, “Who's your favorite guitar player you’ve ever played with?” And he said, “Bob Weir.”

What was Bob’s strength as a boxer?

Bob’s strength was his love of the sweet science. He got it. After that, he didn't really have any athletic skills, except that he knew it was a great workout. He trained hard, but he didn't really have any strengths. He was cool. He ended up working with Phil in the corner for a couple of Phil's fights. I wish I had seen him working a corner of some random fight down in the Valley, wherever they have their little smoker fights. Can you imagine? Bob's in the corner with Phil and the boxer is like, “Who's this old guy in my corner?” And Phil says, “That's Bob Dylan.” And the boxer goes, “Who?” I always thought that would be really funny to see.

Salad Days Ten Year Anniversary Director’s Cut Theatrical Screening

Scott Crawford’s documentary about the DC punk scene is turning ten and a new director’s cut is coming to Braindead Studios in LA on Thursday October 24, 2024 at 8pm. I’ll be moderating a Q&A with Scott and some soon-to-be-announced special guests after the screening. I hope to see you there.

Thanks again for reading — if you’ve made it this far, you’re the best. I’ll be bopping around California for the next week and I’ll fill you in on my adventures next Wednesday. Also, speaking of anniversaries, I’ve got some special events planned for the five year anniversary edition of Message from the Underworld on October 30 so stay tuned!

If you liked this newsletter you might also like my latest novel Make It Stop, or the paperback edition of Corporate Rock Sucks: The Rise & Fall of SST Records, or my book with Bad Religion, or my book with Keith Morris. I have more books and zines for sale here. And if you’ve read all of those, consider ordering my latest collaboration The Witch’s Door and preordering the anthology Eight Very Bad Nights.

Message from the Underworld comes out every Wednesday and is always available for free, but paid subscribers also get my deepest gratitude and Orca Alert! on most Sundays. It’s a weekly round-up of links about art, culture, crime, and killer whales.

What a treat, this was so fun to read, and coming from Pete Finestone no less, a drummer I have probably listened to at LEAST once a week for the last, oh...30 years or so. Most recently just this morning while training at the (non-boxing) gym! Cheers to the both of you