I’ll never forget the first time I saw the night sky at sea.

It was early 1987 and I was serving as a deck seaman onboard the U.S.S. Meyerkord in San Diego. The ship was preparing for a six-month cruise in May.

It was a time of firsts. First experience of Southern California. First time in the fleet. First trip to Tijuana. First underway watch.

One of the main responsibilities of a deck seaman while underway is to perform the duties of a lookout. On our ship, there were two stationed above the signal bridge looking port and starboard, and one on the fantail looking aft. Our job was to scan the sea and sky for anything that might threaten the vessel—other ships, aircraft, boats big and small—and report everything we saw to the bridge.

“Bridge, starboard lookout.”

“Bridge, aye.”

“Contact 040.”

Even if it was just a log floating in the water we called it in because that log might be part of a mast that was still attached to a submerged boat that could damage the ship if we hit it.

(Yes, we had radar and sonar and all kinds of sophisticated technology but we lookouts were a failsafe against mechanical error. If an enemy jet fighter came streaking out of the clouds we’d be dead before we could lift the sound-powered microphone to our lips. But the Navy had always had lookouts and was slow to change. Did we take our jobs seriously? Absolutely not.)

Naturally, these lookout stations were exposed to the elements. Summer sun. Winter nights. Spring showers. Tropical monsoons.

My first day at sea, I was too focused on learning how to do my new job to spend much time thinking about the weather or the view, but that changed that night. The second I stepped topside to my lookout station I was bowled over by the sky.

There. Were. So. Many. Stars.

My first reaction was disbelief. How was this possible?

I grew up in the suburbs. I had seen stars. I could identify the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper and a few other celestial bodies. I saw them in the morning when I woke up well before dawn to deliver the Washington Post. I’d written dumb poems about them as a moody adolescent after walking the family dog on a winter night.

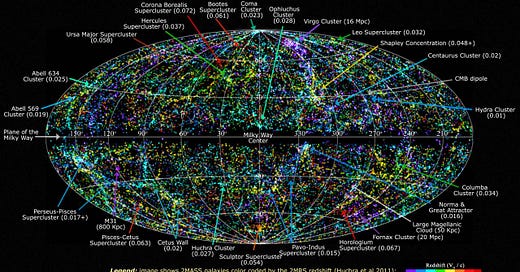

At different moments of my life I was enamored with the stars. Once after I saw Star Wars and became a massive science fiction fan and again in high school when I saw a “You Are Here” map of the universe. I remember staring at that poster for a long time, grappling with the significance of a single human life (namely my own) in a universe with at least two trillion galaxies. To put it another way, the image was too large for my operating system to process.

I knew the cosmos was terrifyingly vast, but I didn’t really know until I looked up at the sky that night.

We weren’t all that far from port, maybe 50 miles or so off the California coast, but far enough that the lights from the cities no longer polluted the sky.

I’d never understood astrological signs. There didn’t seem to be enough information in the heavens to construct those fancy images. Looking up at the sky that night, I finally understood. There was so much material to work with.

Disbelief isn’t quite the right word for how I felt. It was more like the feeling of having been misled, seeing the truth of something that had been obscured for so long that you never thought to question it, a reordering of principles that makes other reassessments necessary, like when a secret comes to light after a death in the family. If the night sky is a lie, what else has been hidden from me? What else am I wrong about? Is anything I believe to be “true” or “real” the least bit reliable?

It was a total paradigm shift before I knew what those words meant.

And shooting stars? I thought it was a figure of speech—and then I saw one. And then another one. And then another. I saw them at least once an hour. It was more remarkable not to see them than to bear witness to those streaks across the sky. But that first one?

Whoa.

I was reminded of all this while reading Ben Ehrenreich’s incredible Desert Notebooks, which I wrote about for the Los Angeles Times.

It’s a hard book to classify because it’s kind of all over the place. I don’t mean that as a criticism but a catalog of subjects Ehrenreich touches on doesn’t really illuminate the book. It’s a hybrid work of nonfiction that toggles between Trump tweets, nature writing, and deep research, but it all works together wonderfully. Ehrenreich’s threads have a way of fusing together, leading the reader to the present moment with deep knowledge of aspects of our planet’s past.

One of these threads is his reckoning with the night sky. After moving to the desert, Ehrenreich begins to experience the stars in a whole new way. This newfound intimacy enriches his understanding of creation stories, leading to an understanding that they were told with the sky as a backdrop and the audience of these stories was intimate with the stars in a way that we’ll never comprehend because, Ehrenreich says, “we messed it up.”

Here’s an exchange in our conversation that was too long and knotty for the profile:

Jim Ruland: I feel like the climax of the book comes during your discussion of pictoglyphs and the realization that many of them function as calendars, and for most of human history it was possible to observe the movement of the stars and planets across the sky each night. Can you talk about that? Was that a discovery or something you always felt?

Ben Ehrenreich: It’s one of these completely obvious things that I as a 21st century human had to discover as if for the first time. I lived in L.A. for 20 years and it’s a good night when you can see 7 or 8 stars. To live somewhere where you can see the night sky, that’s the show every day, that’s it, that’s what you want to see. You wait up for it. You’re excited to see it. When it’s cloudy you’re disappointed. It’s like the movie was cancelled or something. And I’d never been in one place long enough to really understand the movements of the stars, which of course is the movement of the earth, and as I began to do that, I felt this really kind of shocking existential shift. It had never occurred to me before. I mean I knew it, of course, because we all know it. You can see it on shows about astronomy on PBS or you can read enough and still not have it register in your bones that you’re traveling through this enormous universe, and that to be in contact with that, and with the way it marks time, which is still the way we mark time, is to really separate yourself from the extraordinary narcissism that modern urban humans are capable of in which the only kind of time that matters is the one that we’ve constructed, and the only narratives that matter are our own. To step outside of that, to start to understand our relationship to that really messed me up at first in the best possible way. It really upended a lot of my certainty, which needed upending.

Jim Ruland: I had a similar experience in the Navy. The first time we went out to sea I went out on watch and there was no moon. I couldn’t believe it. It felt like a break with reality. Is this real? Is this what the ancients were going on about with all their talk of the stars? It wasn’t until I read your book that I made the connection that maybe the reason there are so many twins in mythology is because of these two stars that side by side in the night sky. None of that had ever dawned on me. One of my takeaways from the book is that while we have access to more information than ever before. We can consume days, weeks, even months of research and reporting just by looking at our phone before we get out of bed, but we know less than we used to. We’re disconnected from the sky, the land, our roots, and our stories. We’re just so disconnected from so many things. Can you talk about that?

Ben Ehrenreich: Yeah absolutely. By not being aware of the stars and not thinking of them, there are a million myths and stories from all over the planet, some of them very old, some not very old at all, that we understand a tiny fraction of because we don’t understand them as narratives that exist in relation to the stars and that track the movements of the stars. The stories that people told one another were also stories that described their place in the universe. Were also ways of understanding time. And yet I talk in the book about beginning to understand that some of the petroglyphs seem to also play that function and mark the movements of the stars. Suddenly they become a lot less mysterious. And at the same time a lot more profound. I guess what I’m suggesting is that one of the things this means isn’t that we’re not aware of Venus is rising in the morning or the evening or what phase the moon is in, but to suggest our understanding of what a story can be to use words to describe our place in the world is incomplete because we can only think in terms of other words and other stories and not these celestial galaxies that people for almost all of human history have been relating themselves to. It was only beginning in the late 19th century, less than 150 years ago, that the skies over most cities became so polluted that we couldn’t see the stars. So approximately 400,000 years before that, people were constantly looking at, thinking about, talking about, writing about, the movements of the heavens, and we are these weird cripples who have just arrived on the scene and can’t see any of that because we messed it up.

Ehrenreich’s response is all the more impressive when you consider that he delivered it verbally with a crying baby in the background around dinnertime in his Barcelona apartment.

The “twins” I reference above are Castor and Pollux. Pollux has a planet called Thestias, which was discovered on Bloomsday June 16, 2006 by Artie Hatzes. Thestias is one of the nearest extrasolar planets and is just 34 light years away. It is 2.3 times the mass of Jupiter and is one of over 4,000 extrasolar planets. Thestias is a patronymn of Leda the daughter of Thestius. Pollux and Castor were sons of Leda, Queen of Sparta. Castor had a mortal father (that’s why it’s the dimmer of the two) and Pollux was the son of Zeus). Pollux’ sister was Helen of Troy.

Got all that? Because my head exploded fourteen times while compiling that, especially the part about the star that has been visible for all of human history and ostensibly pre-history and responsible for so many myths in Mayan, Navajo, Greek and who knows how many other cultures, and orbiting that star is a planet so massive that 3,000 earths could fit inside it, and we only just discovered it, like, 15 seconds ago.

We. Don’t. Know. Anything.

We are like dogs barking poems, which is a discredit to dogs, because they aren’t fucking up the planet. Humans are. (Sorry, dogs.)

If you like your brain bent and your mind stretched in interesting ways, then Desert Notebooks might be for you.

Cat Sitting in Hollywood

Speaking of pets, some of you recall the weird period of my life when I was living in San Diego and working in Los Angeles. I’d stay in L.A. during the week and return to San Diego on the weekends. I never rented an apartment or got my own place. Instead I made do by pet sitting, which was very strange. I also crashed at Razorcake HQ a lot, but that’s a story for another day.

I’d lived in L.A. for about a decade before moving to San Diego to work in an Indian Casino for five years. So I knew L.A. pretty well, but it was weird to move around the city, stay in a new place for a week or two or sometimes longer, and then move on. I’d find a coffee shop I liked or get comfortable with my new commute and then everything would change again. I did that for over a year-and-a-half.

Despite all the driving I did, it was an extremely creative time for me and I wrote a bunch of stories that were informed by my experiences as an amateur pet sitter. They all had to do with the care and feeding of other people’s plants and animals. I published many of these stories, and hope to put them in a collection some day, but one of the earliest, and perhaps most earnest, of these stories was just published by Action, Spectacle.

It’s called “Cat Sitting in Hollywood” and was inspired by a pair of cats named Bob and Ms. Bobo I looked after at an apartment in Little Armenia around the corner from Jumbo’s Clown Room. Caveat emptor: it’s about a poet, which is probably a deal breaker for many of you, and I can’t say I blame you one bit.

Do What You Want Update

I only have one update this week and it’s a doozy. In next week’s newsletter I will be holding a limited edition giveaway. The terms of the giveaway will be announced in the newsletter and to enter you will have to reply to that newsletter so please hold off on your questions. All will be revealed next week. Longtime readers know when Message from the Underworld typically drops so keep your eye out for it because it will be a first come, first serve kind of deal.

In the meantime, if you haven’t preordered Do What You Want, what are you waiting for?

I love your quote about there being so many stars. And this one too from Ehrenreich: "By not being aware of the stars and not thinking of them, there are a million myths and stories from all over the planet, some of them very old, some not very old at all, that we understand a tiny fraction of because we don’t understand them as narratives that exist in relation to the stars and that track the movements of the stars."

And because I'm so slow sometimes, I'm barely understanding Substack. Thanks to you, I launched my own! I had meant to tell you that after I inquired about an op-ed for the LA Times, I didn't need to. Christopher Knight had already been writing about my essay and some of the topic in it. I was floored! Anyway, I migrated over. Thanks for being an inspiration in so many ways. I'm usually a quiet lurker, but not today. And wow, yes, so many stars!

I loved this post but the links to "Cat Sitting in Hollywood" didn't seem to work for me. Is it me or us something amiss?