How have you been? I’ve been feeling pretty shitty lately. I’m at the end of a mild bout of vertigo (knocks wood) and last week I got the Pfizer booster shot, which knocked me on my ass for a few days. The symptoms started slow and piled on: tired, achy, cold. Forty-eight hours later they were gone. It was like I was never sick at all, which, I suppose, I wasn’t.

Today I want to talk about selling out. I reviewed Dan Ozzi’s book Sellout for the Los Angeles Times last week. I’d like to unpack that review a bit and expand on a few things that I didn’t get a chance to talk about.

The book profiles eleven bands that rose from indie obscurity and signed with major labels between the years 1994 and 2007: Green Day, Jawbreaker, Jimmy Eat World, Blink-182, At the Drive-In, The Donnas, Thursday, The Distillers, My Chemical Romance, Rise Against, and Against Me! Because I was a person with ears in the ’90s and ’00s I’m familiar with most of those bands and a fan of a few of them.

The late ’90s/early ’00s were some of my most active years as a participant in the punk scene, but for the most part I wasn’t listening to the bands that Ozzi writes about in Sellout. I was more likely to be at a horrible bar, hoping my favorite band from Dirtnap, Hostage, or In the Red Records wasn’t too fucked up to play that night. Sure, I went to my share of Warped Tours and I’m not going to pretend I never set foot in a Hot Topic, but I didn’t get my punk rock at the mall. No.

The band in Sellout I felt the strongest emotional connection with was Jawbreaker. I was a fan of the band before they signed with Geffen in ’95. It’s possible I listened to Jawbreaker the year I was a coffee jerk in LA in ‘93, but I’m guessing Todd Taylor turned me on to them in Flagstaff, Arizona. If not in ’94 then definitely in ’95 when we were roommates on Happy Street. Neither one of us was writing for Flipside yet. We were just a couple of post-post-adolescent punks enrolled in an unremarkable graduate program.

I remember thinking that 24-Hour Revenge Therapy was much better than its major label follow-up Dear You. That was the prevailing wisdom anyway: the production on Dear You was too slick, and that 24-Hour Revenge Therapy had more heart. Songs like “Condition Oakland” with its rumination on railroads and Jack Kerouac voiceover was irresistible to a couple of dipsomaniacal English majors with more ambition than common sense.

Climbed out onto my roof

So I'd be a poet in the night

Beat the walls off my room

I saw the big room that is this life

This shit was like crack to me. Secretly, I must have loved Dear You just as much because I got all charged up while listening to it last month. I knew all the songs and most of the words. What happened? Did I lose the CD and just forget about it? Was I smoking too much weed during this period of my life? Honestly, I’ve always been like this. My favorite band is usually the one I discovered last week.

I don’t have much to say about the other bands, although I do have a Green Day story. I was at a festival somewhere and Green Day was on the bill. Sometimes I’d get a photo pass and it was always easier to sneak backstage with a photo pass than a media wristband. About mid-way through the set, Billy Armstrong hit a clam and stopped the show. “Oh jeez, I don’t even know how to play my own songs anymore! Anyone want to give this a try?” Then he randomly picked some kid out of the audience to come on stage and play the song and wouldn’t you know the kid ripped it up! Amazing!

I was standing next to someone from the festival staff who just shook his head. “They pull this shit every show and the fans eat it up,” he said.

“Oh?” I said, hoping it wasn’t too obvious that up until a few seconds ago I was one of those shit eaters.

“He’s a ringer.”

Of course he was. The kid on stage handed the guitar back to Armstrong, lifted his arms in victory, and dove into the crowd. Apparently, they’re still doing it.

Whether you think this stunt is pop punk at its most inauthentic or an example of good showmanship will probably determine your enjoyment of Sellout.

The definition of selling out that Ozzi uses is very limited: indie bands signing with major labels. Ozzi starts with Green Day, whose meteoric rise became the major label benchmark for punk bands breaking into the mainstream. Green Day is a great place to start because of the backlash the band faced from Gilman Street punks whose well-meaning rules disguised a puritanical obsession with policing punk for which Maximum Rocknroll was infamous.

Incidentally, Green Day wasn’t the first punk band to sign with a major—not by a long shot. (Readers of Do What You Want will recall that Bad Religion had signed with Atlantic when the two bands toured together.) But prior to Green Day, the concept of selling out applied to a broad range of behavior. You and your band could get branded as sellouts for countless offenses big and small and never get close to a major label deal.

Do I wish that Ozzi had spent more time (or any time really) establishing a context for what it meant to sell out in punk rock? Absolutely. But as a reviewer, it’s my job to review the book Ozzi wrote, not the one I wish he wrote. I’m also not going to grouse about the bands he did or didn’t include. To tell the story of a scene means having to leave some voices out. You can track down every player in every band (or try to anyway) but that’s not storytelling. That’s documenting. There’s a place a for that but it’s not the book Ozzi was contracted to write.

I’d love to know how Ozzi really feels about some of these bands. Because while I believe that when Jawbreaker swore it would never sign with a major label, it meant it, and that the decision to sign caused many dark nights of the soul. But after a decade of bands mostly failing to live up to their label’s expectations I found myself rooting for bands to get their comeuppance. Although I have an indie bias, I’m not a purist, but the section where the dudes in Thursday are quoting their own press clippings all these years after the fact as if it meant something then or now was kind of pathetic. Granted, there are many things I don’t understand about Thursday, but still.

Sellout is well-researched, well-written, and achieves what it sets out to do. As I said in my review, it’s an engrossing read, which transcends feelings of whether I liked it or not—and I liked it a lot.

As a writer, I understand that a reader may not like what I have to say or share the same conclusions that I reach, but if they engaged with the material and it challenged their thinking, then the book has done its job. Or, to put it another way, Ozzi understands the assignment. I hope he writes more books and if he does I will read them.

PssSST! (Sellout Edition)

You know who knows something about selling out? Henry Rollins, that’s who. That sounds like a set-up for a put-down but I promise you that it isn’t. I think Henry Rollins is one of the most fascinating writers of my generation.

Henry Rollins has been called a sell out pretty much his entire career. Everyone knows that before Rollins was Rollins he played in the band State of Alert prior to joining Black Flag. When he played Washington, DC, with his new band for the first time, his old friends in the scene called him a rock star and a sellout, which affected him deeply. Here’s what he had to say about it in Get in the Van:

“I learned something that night that stuck with me. I got shit from some of the people I thought were my friends. They told me that I had become some kind of a rockstar. The fact that I left Washington DC and came back in this “big” band was a sell out. Some people I knew treated me strange. It hurt at first, then I realized something. You’re going to do what you’re going to do and that’s all there is. That’s all you got and that’s that. From that night on I figured they can go get fucked.”

This is the Rollins I love. Vulnerable, reflective, assertive. He uses his intellect to protect his feelings and forge a new way of being in the world. This is a place that some people struggle to reach all their lives. The entry is dated December 3, 1981, nearly forty years ago. Rollins was 19.

When Rollins was in SOA, he had a job as a manager of an ice cream store, an apartment, a bank account, and a record player with a record collection, but he gave up all of those things to be in Black Flag. The band’s bare bones touring operation is the stuff of legend, largely because of Rollin’s diaries from those days, but the conditions at SST HQ weren’t much better. It was a vagabond existence where things like shelter, food, clothing, heat, etc.—things Rollins had taken for granted—had to be negotiated almost every single day.

The life he led as a member of SOA was cushy compared to his life in Black Flag, and yet Rollins was a rock star? No, Rollins sacrificed everything to be in Black Flag.

The sellout wars are battles of perception and Rollins learned earlier than most that it’s a war you cannot win. The things you do matter. The things others say do not.

Rollins wasn’t the only one who was accused of selling out. After Black Flag released “TV Party” Ginn was asked by We Got Power if the band had sold out.

This question was a bit thornier because of Black Flag’s entanglement with Unicorn, a label with a distribution deal with MCA. The single, which Black Flag re-recorded, was co-produced by people attached to Unicorn, such as Daphna Edwards, who ran the label, and Ed Barton, who’d worked on many of War’s hits. The single’s lyrics differ slightly from the version recorded for Damaged, mainly to update the TV shows and schedules referenced in the song. (When Dallas moved from Friday to Wednesday night, Black Flag was on it!)

But the reason why people thought Black Flag was selling out with “TV Party” had nothing to do with Unicorn’s major label affiliation and everything to do with the way it sounded. The song is humorous and references pop culture. Also, there’s a clap track, which is always weird. When a punk band puts a clap track in a song it’s fair game to ask, “What were you thinking?”

“I think TV Party is hilarious,” Ginn replied. “And if we would not do it because we might think we might get some criticism, that would be selling out, rather than saying, ‘Well, we’re gonna do what we like.’

But the questions about selling out kept coming. Rollins came to despise doing interviews. He hated the way fanzine interviews were stripped of context or magazine articles always had an agenda. He just wanted to say what was on his mind, but doing interviews made him feel like he was selling himself out.

Is it any wonder he threw himself into spoken word? Rollins’s “talking shows” provided a platform for Rollins to tell stories in his own way without editorial oversight. He could write his books and go on tour and he didn’t have to answer questions about selling out ever again.

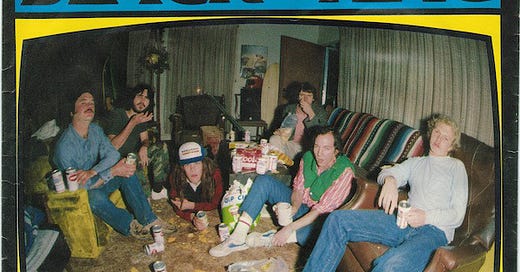

And then this happened.

Miscellaneous Mayhem

Midnight Mass: As a lapsed Catholic and recovering alcoholic who is negotiating the loss of a loved one, Mike Flanagan’s supernatural story about the limitations of the mortal body hit me really hard. It’s not like any horror story I’ve even seen and it unfolds like a novel. I think its set-up is better than its pay-off but it was a hell of a ride. Highly recommended.

Curious Creatures: My friend Lol Tolhurst, formerly of the Cure, has a new podcast with his friend Budgie, formerly of Siouxsie and the Banshees. Together they share stories and reflect on being “elder goths,” which I find endlessly endearing.

Stay safe and be well.

This is great. I'd totally forgotten about that GAP ad. I'm about halfway through the Ozzi book myself. It is striking how he discusses the criticism of "selling out" with bemused bewilderment and tends to frame the desire to protect and nurture independent DIY scenes as "idealistic" instead of, oh I don't know, "principled." But it's definitely an engaging read. But, wait, you're friends with Lol Tolhurst?!?!? Can we talk about *his* autobiography? Finished that a few months ago.

I only had time to skim this and I already love it. Glad I found you. I'll tell you the story of Rollins and I briefly discussing TV Party soon.