I was eight years old when I watched the miniseries Roots on TV.

I had a fairly sheltered childhood. My dad was a naval officer. My mom was a nurse. We moved around a lot and I grew up in the suburbs around Navy bases. New York, Rhode Island, Florida, Virginia. It’s all pretty much a blur.

I remember a dog we had in Jacksonville named George. In Virginia Beach we lived near a lake next to a landfill that everyone called Mt. Trashmore. Then we moved to Falls Church just across the Potomac River from Washington D.C. and that’s where I fell in love with history.

We went on lots of field trips to the Air & Space Museum, the Lincoln Memorial, the Washington Monument, the Smithsonian. All that marble and old stone impressed the hell out of me.

I had a wonderful history teacher named Mrs. Kelly. She was an older lady, at least she seemed old to me then, with a grandmotherly vibe and a real passion for history. She taught me that I didn’t have to wait to go on a field trip to learn about our nation’s history, that there was plenty of history in Falls Church.

She was right. Our little city was founded in 1699, a number that used to boggle my tiny little mind. How could there be a city before there was a country? How did that work exactly?

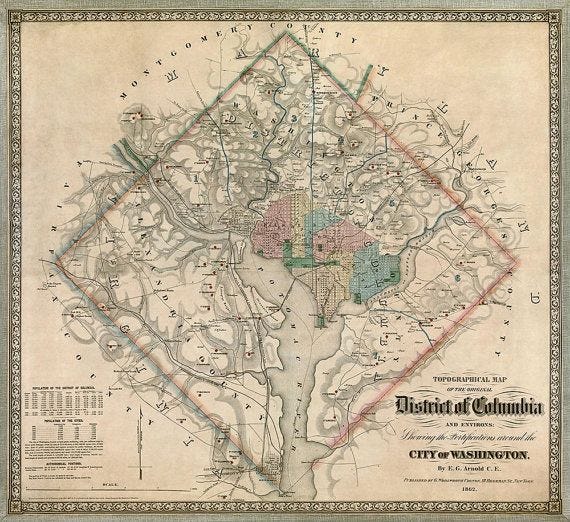

Mrs. Kelly taught me that parts of Falls Church used to be part of Washington D.C. The District of Columbia was initially laid out like a square with each side measuring 10 miles.

D.C. was divided by the Potomac River, the land to the east of the Potomac was called Washington County and the land to the west was called Alexandria County. Originally this land was part of Maryland and Virginia, respectively. The federal government paid off the states’ Revolutionary War debts for the rights to the land. But D.C. neglected the smaller Virginia side because of its fondness for slavery. So on July 9, 1846, D.C. deeded the land west of the Potomac back to Virginia, a process, I just learned, called retrocession.

The old D.C. border was marked by a series of boundary stones, one of which lay in Falls Church.

“Is it still there?” I asked.

Mrs. Kelly didn’t know. So I went to the library, looked up the address, got on my bike, and pedaled my ass over to the old stone marker.

It was still there.

That’s the kind of kid I was. We couldn’t drive past the car dealership that’d been the site of a Civil War battlefield or the house where Eisenhower lived before he became President without me announcing it to everyone.

I was the kind of kid who read Encyclopedia Brown books as aspirational texts. Today I uncover old historical markers, tomorrow I’ll solve crimes…

Then in January of 1977, I—along with millions of others—watched Roots. It was unlike anything I’d ever seen. But even by today’s standards it was a unique television event.

The miniseries ran for eight consecutive nights. The epic begins with Kunta Kinte being abducted from his home in West Africa and sent across the sea in shackles. He lands in Annapolis, Maryland, where he’s sold at a slave auction to an owner who takes him to Spotsylvania, Virginia. Each step along the way things just keeps getting worse for Kunta Kinte.

I was horrified. I thought I knew what slavery was. We were taught a sanitized version of the Civil War at St. James Elementary, the Catholic school I attended. Slavery was bad, there was no question about that, but it was also a historical fact. There were slaves in the Bible, too.

But watching the series unfold as Kunte Kinte was whipped and beaten again and again inflamed me. Couldn’t they see this was a human being? Did the color of his skin make his tormentors blind to his humanity?

Confronted with the gritty reality of slavery, the constant brutality and degradations, I couldn’t get over its wrongness. I felt like I was witnessing a crime and not the representation of one.

I think the show’s format is what made such a lasting impression on me. Each night I had to decide to sit down and watch the next installment, and each day I thought about what I’d seen the night before.

The fact that parts of the show were set in Virginia and Maryland also resonated. This wasn’t something that happened in a faraway land in a faraway time. It happened right here.

Roots woke me up to the fact that trauma is never just a fact of history. It shatters families and wrecks communities, and when there is no reckoning, the trauma festers and is passed on to the next generation.

Roots, more than anything else, taught me empathy. Critical thinking would come later, but I needed to walk in the shoes of a young man who’d been taken from his home and stripped of everything he had—even his name. My education didn’t ask me to wonder what that life was like, but Roots did. I needed to see it to understand the paradox of racism: In order for a human to mistreat another human being they have to view the object of their derision as less than human, but the cost of denying someone their humanity is to sacrifice one’s own.

This was so clear to me as an eight-year-old. Why wasn’t it clear to everyone else?

I’m still wrestling with that.

I don’t know how Roots holds up today. The show won 9 Emmys, a Golden Globe, and a Peabody Award, but I can’t think of a show or television event that could unite this country the way Roots did in 1977. We’d spent a year celebrating the greatness of the U.S.A. during the bicentennial, and then Roots came along and said, “Not so fast.”

But I think of all the eight-year-olds around the country who are learning about the racism that makes the murders of men and women like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner and so many others possible, and in some cases, inevitable. I see them making signs and marching in protests and I feel something like hope because they are learning about racism not as a historical fact, but as a component of justice.

1000 Memories with Milky McSkim

Milky McSkim (aka Julie) is one of four active administrators for The Bad Religion Page, which means her fandom runs 24/7. She helps coordinate giveaways sponsored by the band. Since COIVD-19 hit she’s been focusing on raising money for charity, including a recent promo that raised over $4,500.

Jim Ruland: What’s your favorite Bad Religion album?

Milky McSkim: In ‘94 I was at the Ice Chalet in Costa Mesa for hockey practice. There was an amazing record store in the back of the rink and they were just about to release Stranger Than Fiction. I was already a huge fan, but didn’t have enough money for the release. After practice that day, my dad saw my disappointment and offered to pay half of the album (I had exactly the other half). We spent many years sharing that album. “Hooray for Me” became my personal theme song and still fits perfectly all these years later, and the album remains my favorite for the music and the memories.

Tomorrow we’ll be exactly two months away from the release of Do What You Want, the book I co-wrote with Bad Religion. Are you excited? I’m excited.

In fact, this morning it was announced that there’s going to be a version of Do What You Want in Italian from Sabir Editore.

If you missed it, here’s an interview I did about the book that ran in several SoCal newspapers.

If you haven’t pre-ordered Do What You Want, there’s no time like the present.

Hi Jim, i'm Giorgio Arcari, editorial director of Sabir. We're already working on the translation and we're very excited too: we love what we are reading! Next year Bad Religion will be part of Bayfest in Bellaria, ten minute from our place. We'll be there, maybe you will come too. If so, it could be a great chance to talk about the book in a great punk rock festival and, of course, you'll be our guest.

Will you be doing readings in Italian?