It felt like a flashback to a better time. I was in Strange Daze books in Barrio Logan when Andres, one of the proprietors, handed me a DVD.

“Have you seen this?”

“No,” I said.

It was the uncut special edition of Ichi the Killer directed by Takashi Miike in 2001.

“Take it,” he said. “You have to see this.”

The film came with a blurb that read like a warning:

“Ichi is probably the Citizen Kane of arterial spray movies, or at least the Casablanca.”

If you’re in a used bookstore and someone hands you a VHS tape or DVD, and says, “You have to watch this,” you have to watch it. This is how we found out about weird shit before the Internet. Even though the phrase “arterial spray” gave me pause, these are the rules.

True 40 years ago. True today.

But because it’s not 2001 anymore the only DVD player I own is the one gifted to me by my mother before she passed. It’s a Toshiba portable DVD player and was manufactured in April 2004. The screen is 3” by 5”—the same dimension as an index card—and it weighs more than a stack of laptops.

Ichi the Killer is technically a gangster film but a very strange one. The gangsters belong to one of two warring factions but they all conveniently live in the same apartment complex and are constantly spying on each other. When one of the bosses disappears a war erupts between the two factions, which is basically an excuse for the extreme violence that Miike revels in.

How extreme? Many people regard Ichi the Killer as a horror film because of the truly outrageous amounts of gore and difficult-to-watch scenes of torture and rape.

I’ll try not to get too deep into the byzantine plot but the movie boils down to a face-off between Kakihara, the missing gangster’s sado-masochistic lieutenant, and Ichi, his boss’s killer. Ichi isn’t a person so much as the alter ego of a creep who gets sexual satisfaction out of acts of violence he is powerless to control. But Ichi isn’t a gangster. He’s a civilian who is so timid and fearful he has to be manipulated into killing by a mysterious handler who places him under hypnosis. When he’s not killing, he’s crying.

Ichi wears a black rubber bodysuit equipped with razor-sharp knives and when he turns into a whirling dervish of martial arts the blood sprays like a firehose. During one of Ichi’s kill-crazy freak outs, a sliced-off face splashes on the wall like a busted tomato and slowly slides to the floor.

It’s a lot.

Over the last few weeks I’ve watched the film repeatedly, the whir of the DVD keeping me company in the studio, and I’ve come to think of Ichi the Killer as a very bleak and very dark existential comedy.

In any other movie, Kakihara would be the villain, but Ichi is so loathsome in his torment that Kakihara assumes the mantle of hero. The audience yearns for Kakihara to kill him because even though Kakihara carries around a quill of needles that he is fond of sticking into his victim’s faces he is clearly the lesser of two evils. (He doesn’t harm women, for one thing.)

The world, even one as disgusting as this one, would be a better place were Ichi not in it. Even though it’s called Ichi the Killer it’s Kakihara who graces the cover. He’s the anti-hero we want to see come out on top.

The film operates as a parody of ultra-violent martial arts movies where people punch and kick and stab and slice each other to little effect. There’s very little fighting in Ichi the Killer, but lots of people dying with gallons of blood pooling on floors cluttered with bodies. Where most martial arts movies are tidy, this one is an unholy mess.

Is Ichi unwatchable? For some people, yes. Some people might say that it should be. In fact, it has been banned in several countries and during its theatrical release theaters handed out barf bags to patrons.

If this movie came out today and was made by a Westerner, I don’t think I’d watch it. Ichi the Killer is an adaptation of a Japanese manga of the same name. I’m no expert, and I haven’t read Ichi the Killer, but in manga there’s a tolerance for the extreme that runs from the pornographic to the grotesque for which there is no equivalent in Western culture. (I think the only mainstream phenomenon that comes close to combining the psychosexual horror of some manga is true crime but that’s an argument for another day.)

So the story gets a pass because the extremes of the film echo the extremes of the source material. Certainly, Miike understands that if he wants to make a statement about the way society has turned us all into voyeurs of the grotesque, he can make that point more effectively by bringing a story to life that already exists rather than thinking up novels ways to rape and torture people, because the plot is not the point here.

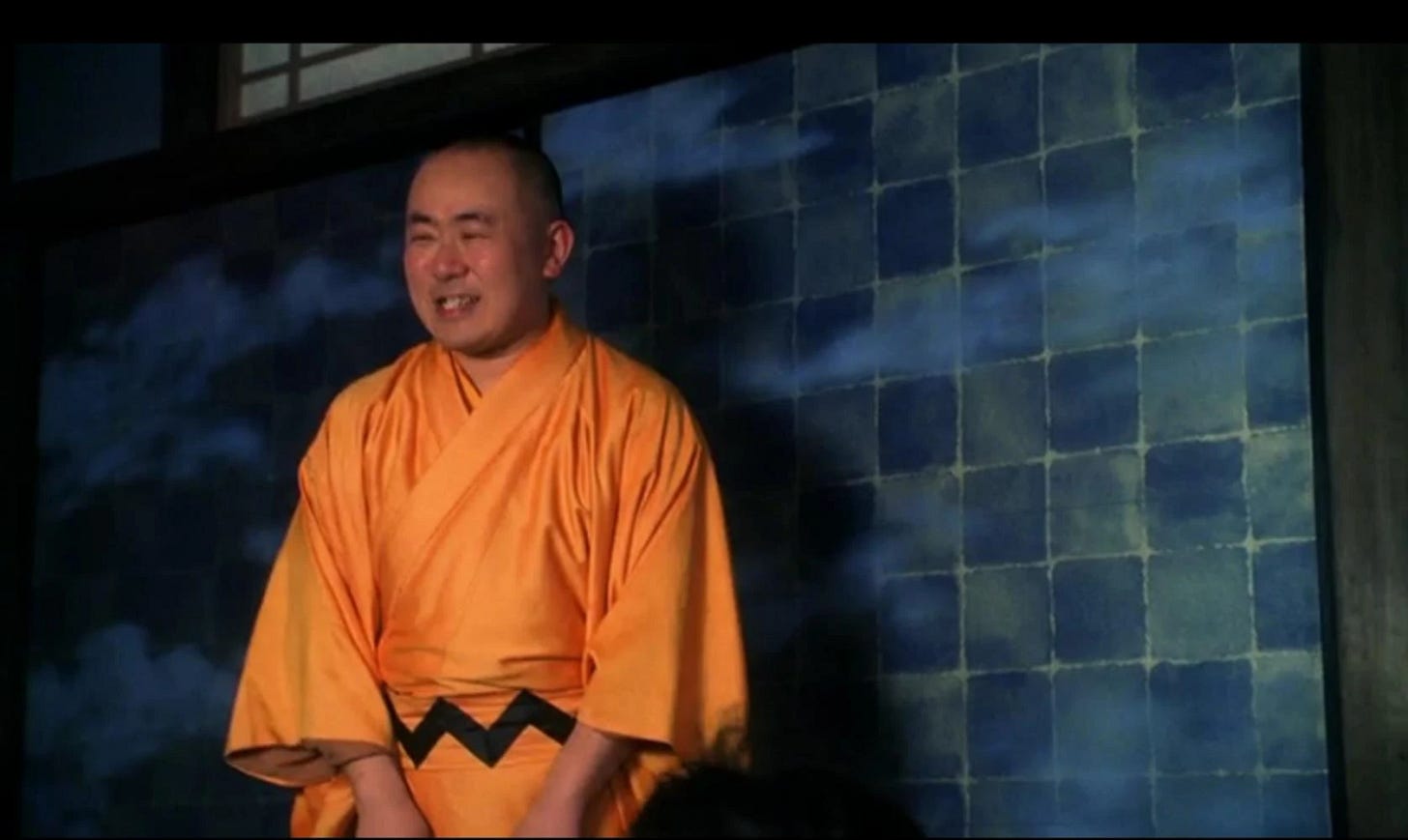

Miike is aware that he’s creating a spectacle. The screenplay was written by Sakichi Satō, an actor, writer, and director who also plays the character Ichi. He is probably best known for his performance as Charlie Brown, a waiter at the House of Blue Leaves in Kill Bill I and II, which by the way is available now on Amazon Prime.

I mention the Tarantino connection because the two directors are very much in conversation with each other. Tarantino has even appeared in one of Miike’s films, Sukiyaki Western Django. The difference between the two is that Tarantino obsesses over his films and fills them with obscure references. Miike shoots his in two weeks, which is why he has over 100 credits to his name. It might also be why his films become obscure references.

I’ll admit, some of what I find funny about Ichi the Killer is unintentional. The version on the DVD is dubbed by English actors and the gangsters all have East End accents, which is hilarious. “Oi, Ichi, come back here, you wanker!”

I am fascinated by the ending of the film. Kakihara and Ichi finally meet in a rooftop showdown but when Ichi kills an interloper in front of the man’s child he is so besotted with grief he falls to the ground and weeps. No big climax. No final battle. Kakihari literally begs Ichi to get up and fight but he refuses.

Instead of killing Ichi, he takes his razor sharp needles and inserts them into his own ear canals because what he really craves is death.

“No one left to kill me,” Kakihara says as he surveys the scene.

And then things get really weird. As the needles slide deeper and deeper Kakihara enters what can only be described as an alternate universe where he gets what he desires most.

Ostensibly, the theme of the film, like the theme of all gangster films, is revenge, but Miike is clearly going for something deeper here. The players are arranged on the stage as in a Shakespearean tragedy where revenge is demanded and exacted until there’s literally no one left standing. Miike calls the viewer’s bluff. “Revenge is what you claim to have come for, but there are other reasons why you stayed.” Each viewer will have to make their peace with that.

Horror is a place where one’s emotions are cast into sharp relief. We know exactly what to feel in a slasher movie—fear of the villain, empathy for the victims—and the experience becomes a crucible for testing our tolerance of how much we can take. For some, there is comfort in knowing exactly what to feel—even though those feelings are dialed up to 11.

This is different. Something much more difficult to define is being measured.

The trailer plays to the spectacle and hews to the plot, but it teases the darkness that lies in store. Don’t say I didn’t warn you…

I’d hoped to go into several more films today, but Bouchercon is in town this week and I’ve got to run. Would you like to see more of these reviews?

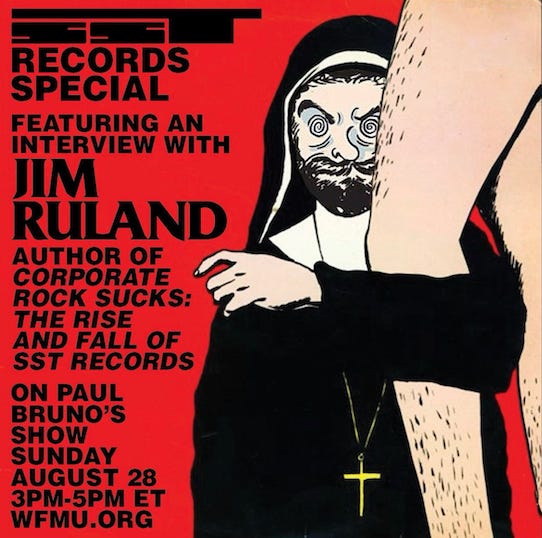

SST on WFMU

Earlier this month I recorded an interview with Paul Bruno for his radio show on WFMU and he put together an excellent playlist of deep SST cuts with lots of inspired selections. The artwork isn’t bad either—check it out!

Have fun and see you next week. Remember, paying subscribers to Message from the Underworld also receive Orca Alert! every Sunday.

WUOO LOVE THE PLAYLIST! 🙌

I'll take more reviews! Do you have Letterboxd?