Warning: This edition of Message from the Underworld contains spoilers for the movie Get Out.

I’d just started reading Jordan Peele’s Oscar-winning screenplay Get Out from Inventory Press when I heard the news that Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died.

It felt like a punch in the gut. The repercussions were immediately apparent: Ginsburg’s death would trigger a paroxysm of anguish on the left, and a power grab on the right, with the net result being increasing feelings of helplessness as our country slides further into authoritarianism.

Like being in the Sunken Place, except for the whole country.

But the deeper I got into Peele’s screenplay, which comes with photos, deleted scenes, 89 endnotes, and an introduction by Tananarive Due, it started to dawn on me how wrong I was.

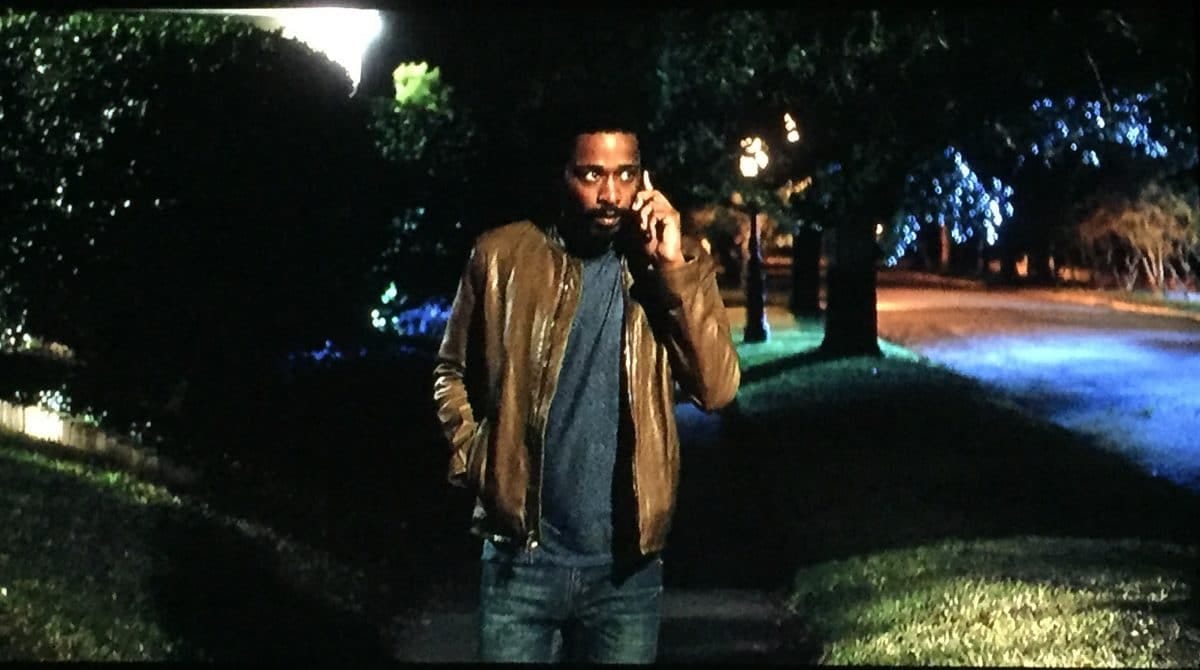

Get Out opens with an abduction. A black man named Andre walks down a leafy suburban street. He’s a city person, Peele’s screenplay tells us, and he’s a little creeped out by the dark, tree-lined streets.

Andre is frustrated because he thinks he’s trying to get to Evergreen Street when he’s supposed to be looking for Evergreen Place. Here’s what Peele has to say about this scene:

“I knew that a lot of people didn’t understand the fear that a Black person has when in a neighborhood where he or she might be presumed to be the monster. I was trying to capture that fear by forcing the audience to walk through a neighborhood they did not belong in.”

Reading Peele’s note, I thought about an experience I had in 2005. My first book, Big Lonesome, had come out that summer and I’d arranged to read at a community bookstore in Minneapolis while I was in town on family business.

2005 doesn’t seem like that long ago, but my rental car didn’t have a GPS and I didn’t have a smart phone. All I had were the directions I’d printed out on MapQuest back home in L.A.

I got lost in the most confounding way possible. I was on the right street, but I couldn’t find the bookstore. It quickly became apparent I was in a residential area in a Black neighborhood and some of the cars were rundown and some of the houses were boarded-up and it was so dark it was difficult to see the street addresses and running underneath my thoughts like a current was the feeling that I didn’t belong there.

Did I feel this way because I was a white person in a black neighborhood? Yes, absolutely, that was part of it. I’d traveled all over the world and every major city had neighborhoods you didn’t go to into unless you had a reason for being there. Belfast, Mexico City, Manila, and Los Angeles all had neighborhoods like that. Why would Minneapolis be any different?

This didn’t necessarily mean I was in the wrong place. The bookstore I was looking for was a co-op run by punks. This could be the place, but it didn’t feel like the place, and if I didn’t find it soon, I’d be late for my reading, which for me is a direct line to anxiety.

By the time I pulled over and parked the car, I was pretty certain I was in the wrong place, but I was determined to see this through and verify with my own eyes before moving on. I didn’t want to succumb to fear. I wanted to prove I was better than my biases.

But now I was flustered. Do I bring my books or leave them in the car? What about my travel bag? Do I need my jacket? I was focused on all the wrong things.

I got out of the car and opened the trunk. I put my travel bag inside and took out my jacket and stuffed my pockets with books. I shut the trunk and headed down the street. Do I have everything? Books, wallet, keys. Shit. Where were my keys? Please don’t tell me I locked the keys in the trunk of my rental car ten minutes before I’m supposed to give a reading.

I headed back to the car, scanning the ground for my keys along the way. By now I could sense movement on the street. People communicating with each other in the distance. Someone coming toward me.

A Black man in his thirties approached. I don’t remember what he said. “What’s up?” or some variation.

“I’m looking for a bookstore,” I said, “but I dropped my keys.”

He reached into his pocket, pulled out his phone, and turned on the flashlight, illuminating the ground at our feet. I didn’t even know phones could do that.

Someone called out to the man with the phone and he yelled back, “He’s looking for his keys.” With the aid of his phone we found them, which I couldn’t believe because I was certain they were in the trunk.

I asked the man with the phone if I was on the right street. I was, but after looking at my map he explained I was on the south end of the street when I needed to be on the north end, which was on the other side of town. Mystery solved. I thanked him and left.

I got in my car and drove away feeling a queasy mixture of guilt and relief. Had I oafishly blundered into a sketchy situation that I was fortunate to get out of unharmed? Or had my biases caused me to see a normal neighborhood as something more sinister?

Jordan Peele’s Get Out screenplay is a cool-looking well-designed product. It’s for people who have seen the movie and want to study it and think about it. It’s a black and white paperback without any slick insert pages. Rather, the photos are scattered throughout the text. The deleted scenes are clearly marked with the page number where it’s located at the end of the book. I wish the endnotes were a bit larger but that’s my only complaint. It’s affordably priced at under $20; basically the opposite of Ari Aster’s Hereditary screenplay from A24. It has the feel of book you’d pluck off the rack in a grocery story rather than some curiosity you’d find in a specialty shop.

What I love most about the book are the endnotes. Peele walks the reader through his thought processes. Sometimes he takes us to early in the first drafts (he started it when Obama was president) sometimes he shares discussions with the actors while shooting the film (when Trump was president).

It’s like sitting in on a guest lecture in an advanced screenwriting class. My biggest takeaway from these notes is how he’s always thinking about the audience. Is the audience ahead of the protagonist or behind? Are they all tensed up and in need of some comic relief? Is he in danger of losing them?

Except for Peele the audience is never an amorphous, nebulous group of people. He’s actually writing for two audiences: the Black audience and everyone else. But it’s even more specific than that: he’s writing for a Black audience sitting in a movie theater watching a horror film, which is a very specific thing with its own freedoms and constraints because he doesn’t want to titillate one audience at the expense of alienating the other.

All writers are masochists because we are brutally hard on ourselves, suspicious of scrutiny, and put our faith in magical talismans. To get better we subject ourselves to the same lessons again and again and again. We fail repeatedly and if we are somehow fortunate enough to solve the problem the solution is something that’s been staring us in the face all along, and the thing that gets us there is often the hoariest cliché imaginable.

So it was an immense comfort to me to learn that Peele spent years working on Get Out without a clear sense of what he was doing or what it was about.

“For a while, I understood the setup but I didn’t know where the story was going or how the horror component would materialize. I just pictured it being some form of torture with some kind of awful conclusion. I’d take breaks from writing for months and then go back and add new elements. There was no real engine behind it—it was just something I was working on and that was teaching me to be a better writer.”

But writing Get Out did more than teach Peele about his story, it opened his eyes to the reality of systemic racism. When he created the concept of the Sunken Place, a place where you have no control over your body and what happens to it, but you can see and hear everything but are powerless to do anything about it, he thought he’d invented a scenario of intense psychological horror; instead he created a metaphor for something even more terrifying.

“So, when I had the image of Chris in this dark hole—two years, three years into outlining this movie, I realized I was talking about the prison industrial system. These people are abducting Black people and throwing them in holes, and we as a society toss them into the back of our minds.”

Fuuuuuck.

As sad as I am about RBG’s death, as angry as I am at the GOP’s hypocrisy, as terrified as I am about what is happening to this country, I have my freedom, and so do you.

We are not in the Sunken Place.

We are free to vote, free to protest, free to donate our money and our time. We are free to affect change in ways big and small.

“Fear is the mind-killer,” wrote Frank Herbert. It makes prisoners of us. That’s what the people who are trying to steal this election want. They want us to be fearful of our neighbors. Fearful of those anarchists in the city. Fearful of those rednecks in the country.

Fear divides. Fear separates. Fear is the voice in the back of your head telling you don’t belong. Fear is a one-way ticket to the Sunken Place.

When Peele wrote Get Out it had a different ending than the one you’re familiar with. In the original ending, the Obama-era ending, Chris goes to jail for the murder of the Armitage family. But after Trump was elected, Peele felt the audience—both Black and white—needed a different kind of ending, something to feel good about.

We did and we do. Let’s do our part to make sure this awful year and nightmarish presidency gets the ending it deserves.

Something You Can Do This Instant

This week I donated to Mark Kelly, husband of Rep. Gabby Gifford, who is trying to flip the Senate seat in Arizona. The winner of this race could be sworn in as early as November 30, making it extremely important in the fight to keep the GOP from ramming through its selection on the Supreme Court. Early voting begins in Arizona in two weeks. Please chip in if you can.