How to Ruin a Reading

Something seemed off from the start.

I’ve been attending San Francisco’s Litquake for the last five or six years. I don’t always go to the keynote events and have only gone to the big party after Lit Crawl once (and that was so I could steal a poster), but I know many of the events are ticketed and sell out.

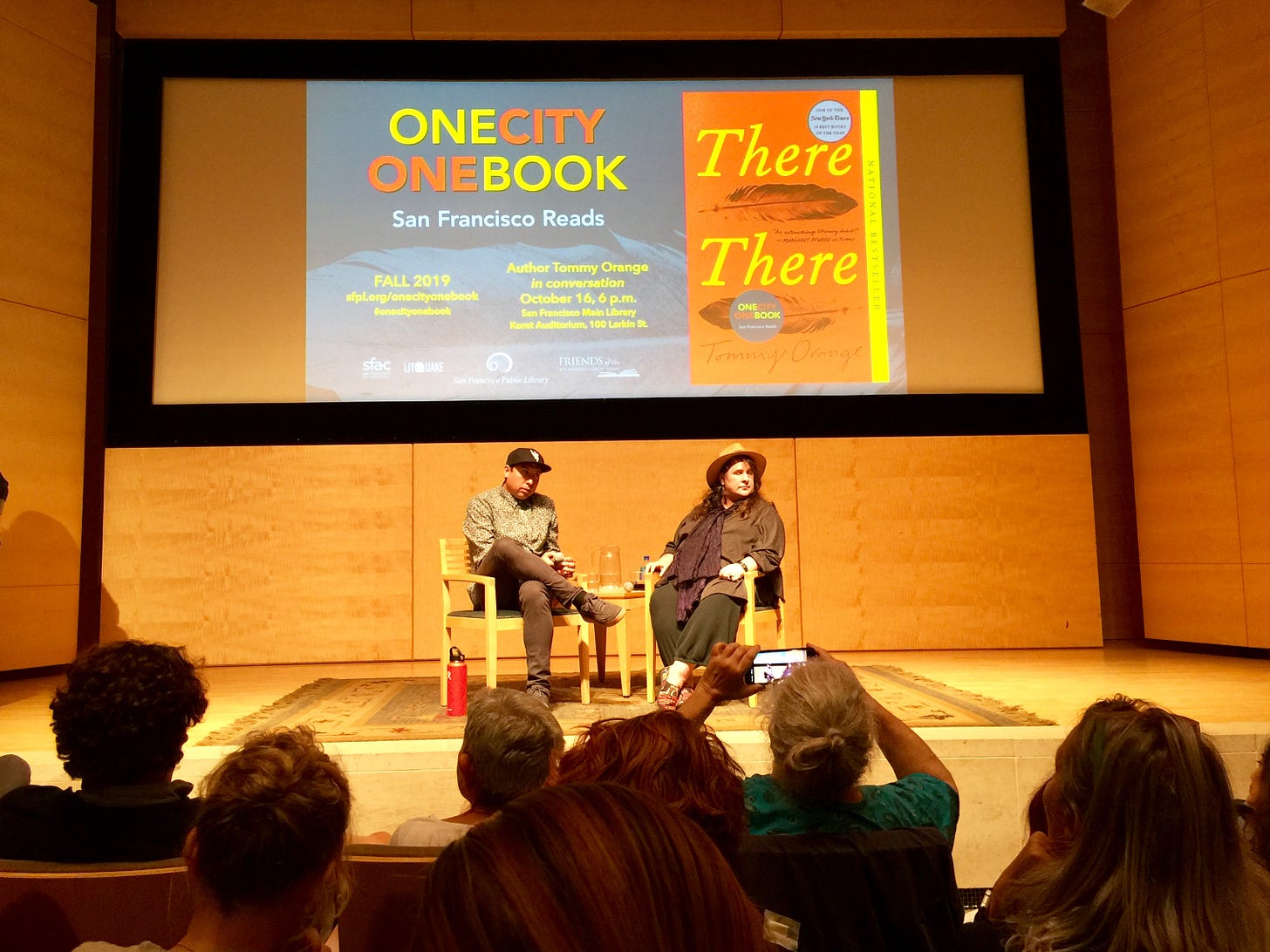

So I was surprised when I read that Tommy Orange’s reading was free and no tickets were required. This struck me as odd because not only is Orange a bestselling local author from Oakland, but his book There There was the San Francisco Public Library’s One City One Book selection. This was going to be a massive event.

I was so convinced this was an error, that as the event approached I checked the Litquake website a second and third time, but the event was still free and open to the public. The venue must be really big, I thought.

It wasn’t.

The Main Hall of the San Francisco Library was actually pretty small. It’s a fraction of the size of the auditorium at the Main Library in downtown Los Angeles. I’ve attended many events there as part of the ALOUD reading series and even though they are usually free, tickets are required.

Why have tickets for a free event? So you don’t have to turn away disappointed literature lovers.

On the day of the event, I debated how early I should arrive at the library. By this time I’d scheduled a phone interview with Orange for the Los Angeles Times. Because of Orange’s busy travel schedule, I was only able to arrange a 30-minute conversation with him. I planned to use his reading as a fact-finding mission to help ask questions that would pique his interest, and I didn’t want to do that from the back of the hall.

I went to the library’s website and learned there would be a book singing before the event. This wasn’t on the Litquake website, but because I knew that Orange would be getting on a flight immediately after the reading, it made sense.

When the friend I was planning on going with backed out, I decided to arrive early. Maybe I’d buy a book, get in the signing line, and introduce myself. But these plans went out the window as soon as I arrived at the library.

The signing line was very long. Not the longest I’d ever seen, but not short. There was also a line to purchase books. With less than an hour to go, the odds were good I could wait in both lines and still not get my book signed.

Instead, I went inside and was shocked by the size of the venue—and not in a good way. I don’t know how many people the Main Hall holds, but there were already more people in the signing line than would fit in the hall, and this was an hour before the event was scheduled to begin.

I went inside and grabbed a seat. To kill time, I listened to some music through my hearing aids and worked on a short story.

The story I was working on is about an angry woman going through a divorce who goes on an assignment to Guadalajara to interview a famous reclusive author. She and her husband were both writers before they ditched their careers and opened a food truck together, which ended badly. She is still processing this when she finds herself in a lakeside village outside Guadalajara where a large number of Canadians have settled. The village is colorful, picturesque, and not the least but authentic. Its brightly painted storefronts and vivid murals were created to appeal to white eyes. This upsets the journalist. White people ruin everything, she thinks as she leaves town, vowing never to return.

The two front rows of the hall were reserved for library personnel. One City One Book is a big deal and I’m sure the selection committee was excited to see the results of their hard work come to fruition. But for a solid 45 minutes before the event, people entering the crowded hall would make their way to the nearly empty front rows, see the reserved signs, take in the packed house, and try not to make a spectacle of their disappointment.

As the hour of the event approached, people stood in the back and lined both sides of the hall. The place was buzzing with anticipation. A lot of people had come out for Tommy Orange. So many, in fact, that the library started sending people to an overflow room where they could watch a video recording of the event. (I’m told the audio and/or video didn’t work, but I don’t know if this was fixed.)

I was seated next to a very nervous and very thin Asian woman on my left and a middle aged white man to my right. As near as I could tell, we were all sitting together alone. After fidgeting with her phone for fifteen minutes, the woman to my left took out a stack of greeting cards and started filling them out. I like to think my scribbling in my notebook inspired her.

Then my least favorite part of an institutional literary event began: the introductions. First the City Librarian of San Francisco spoke. Then a representative for Litquake made their spiel (this happens at every Litquake event), and then finally someone came up to introduce the two participants in the conversation: the Poet Laureate of San Francisco Kim Shuck and Tommy Orange.

If you’ve read my profile of Tommy Orange in the Los Angeles Times, you know that approximately 20 minutes into the show a white woman in the audience disrupted the event. She shot up her hand and said, “Can I ask a question?” Once the authors got over their surprise—this was not the Q&A part of the program—Orange engaged her. “What was your question?” he asked. The woman asked if they could talk about his book. This suggestion was met with approval from a group of people seated behind me I presumed were her friends, but also from a large group of white women seated in front of me.

I was appalled, but Orange pressed on. He asked what she’d like to talk about, to which the woman replied, “Why was the beginning of your book so sad?” Or something to that effect. I didn’t catch the exact wording, but her intent was clear. She wanted to she disrupt the reading of the writer who disrupted her reality.

If you haven’t read There There, you can read the prologue here. It tells the story of a group of people brought to the brink of extinction by another group of people. Fittingly, the prologue explodes many of the myths of the Thanksgiving tradition.

I find the prologue compelling for a number of reasons, but I especially admire the way Orange attacks the lie of a time when natives and white colonizers co-existed peacefully, and this harmonious relationship was denigrated over time by bad behavior on both sides.

Orange was having none of that, and he was as uncompromising on the stage at the Main Hall of the San Francisco Public Library as he is in his book. He called the woman out on her entitlement. He called for a moment of silence for those who’d had their realities shattered. He even went so far as to say, “No more white hands,” which received a mixed reaction from the audience.

I don’t know why the woman felt she had the right to interrupt the event. Would she have done this if Orange was in conversation with a white person? Did the fact that two native writers were on stage make it okay for her to interject her worldview?

I watched all this unfold with grim amusement. I found the conversation between Shuck and Orange up to that point fascinating. How often does one get the opportunity to listen to two very different writers talk about this strange moment in their careers when they are the toast of the town? The fact that they are both from the same part of the world and their families know one another made it all the more fascinating. And as a white, middle-aged man outside of academia, it was an exciting opportunity to listen and learn from a pair of artists outside of my cultural experience.

Their conversation was intimate and at times it felt like I was sitting in on a conversation taking place in a kitchen, and not on stage in a library auditorium, marked by dry wit that concealed an abundance of humor.

But this wasn’t what the white woman who interrupted the event wanted. Nor did the women in front of me care for it, judging by their reaction to the unsolicited intrusion. What were they expecting? What were they looking for? What baggage did they bring to the reading with them? Why should “entertainment value” be an expectation in a dialogue between artists? Why should a conversation between writers be expected to unfold like a game show?

When Orange and I spoke on the phone a few weeks later, I told him I was there. “Oh, you were at that mess?” He laughed and we talked about it a bit, trying to determine the woman’s motivation, and here’s what he said:

TO: I actually think it came from a place of ignorance, she’s just blind to her own sense of privilege. To not understand, to have the gall to interrupt a show not going the way you wanted it, is so much entitlement. And on top of that to ask why I made the prologue so hard for her to read as if I should be thinking of her feelings? White fragility doubled down on the whole thing. I’ve run it through my head a bunch of times. How could it have gone differently? But in the end, it was pretty fucked up what she did.

JR: Yeah, a case study in how not to behave in that setting.

TO: That kind of thing kind of sticks with me. I don’t want it to go down like that. Then I get triggered. Am I taking care of white people?

That remark stuck with me because it’s something I seldom have to consider as a reader, performer, or host. Occasionally, I’ll invite an irreverent reader to my irreverent reading series and they say irreverent things. As a host I try to make sure that everyone is okay without compromising the artist’s right to read the work I’d invited them to read.

But that’s different. I seldom have to consider that my words coupled with my presence on a stage will upset an audience because it goes against the grain of how they perceive themselves. I rarely have to think, This might not go over well because of who I am and who they are.

It’s natural to go to a reading and want something out of the experience: A signature in a book. An answer to something we didn’t grasp. Insight into how the work of art was made.

But maybe that’s too much. Maybe a better approach is to look to what we can give. To celebrate the creation of something new. To offer emotional and financial support. To hold space and not bring our baggage to bear on the proceedings.

It’s tough because our perception of readings is tangled up in commerce. For some going to a reading is always going to be a financial exchange, which then turns the attendee into a customer and the reader into a weird kind of service provider, and the customer is always right, right?

No. Not in the least. Perhaps those people should stay away from readers.

The disruption didn’t ruin the event for me, although it certainly did for some. I thought Orange was spectacular. But it bothers me the first two rows were packed with librarians and people who organize cultural events for a living, and not one of them thought to stand up for the writers on stage. That’s a shame.

It wasn’t Orange’s job to “take care of white people,” but it was the organizers’ job to take care of their guests. And they didn’t. They let them down. It was a poorly organized event from the get go and when things slid out of control they did nothing to stop it.

So the next time you go to a reading and the author seems a touch irritated, consider the many ways we fail artists as a culture and try to remember those failings don’t go away when an artist becomes successful or even famous. If anything, they are magnified.

We can and should do better. Oh look, here are some opportunities to hold space with literary artists in Southern California and beyond….

Lit Pics for 11/28-12/4

Thursday November 28

You’d be hard pressed to find a bookstore or library open on Thanksgiving, but after the parades are over and pumpkin pie has been served, I’m looking forward to reading The Sympathizerby Viet Thanh Nguyen. The Sympathizer made a big splash in 2018, winning the Pulitzer Prize and Andrew Carnegie Medal, but I somehow never get around to reading it. Nguyen recently announced on Twitter that he’d completed a sequel so I figure it’s a good time to catch up. What book has been languishing on your to-be-read pile that you’re hoping to read before the end of the year?

Friday November 29 (SD)

I don’t like the term “Black Friday” but as a member of the Golondrina Collective, I’m technically a small business owner and that means we’re having a sale on Black Friday (10% off storewide) and an even bigger sale on Small Business Saturday (20% off). If you’re in San Diego, swing by the shop in Barrio Logan. Chances are either Nuvia or I (or both of us) will be there.

Saturday November 30 from 10am to 10pm (LA)

Some of my favorite writers will be at Skylight Books for Small Business Saturday to help you select the perfect book for your holiday shopping. Check the link for the schedule of authors, which includes Liska Jacobs, Sarah Gailey, Brandy Colbert, AJ Dungo, and Steph Cha.

Sunday December 1 at 12pm (SD)

On the first Sunday of every month Mysterious Galaxy hosts The Writers Coffeehouse, an informal conversation with local writers talking about the unspeakable horror of the literary life.

Monday December 2 at 7pm (SD)

The Verbatim Poets Society meets on the first Monday of every month at Verbatim Books in the heart of North Park. This month’s event features a canned food drive. So if you’ve got an extra can of yams in your cupboard, you know what to do.

Tuesday December 3 at 7:30 (SD)

Matt Coyle discusses his new novel, the sixth book in the Rick Cahill series, Lost Tomorrows, at Warwick Books.

Wednesday December 4 at 7pm (SD)

Are you fan of the 33 1/3 series of books about influential albums? Do you like MOOG music? What about Switched-On Bach, the highest selling classical music album of all time? If any (or all) of these apply, get yourself to Verbatim Books where Roshanak Kheshti will discuss her book about Wendy Carlos’s influential album Switched-On Bach. This book release will also feature a performance by the synthesizer made famous by Bob Moog.

Thanks for reading Message from the Underworld. Have a wonderful holiday and drive safely if you’re traveling.