I have a bit of good news to share. Last week I mentioned that a friend’s in-laws were both sick with COVID-19. I’m happy to report they’re on the mend and recovering at their home in Belfast.

In the glass half-empty category, my brother Emmett has had his hours at the hospital cut. While this isn’t great news from a financial point of view, he’s grateful for any shift he doesn’t have to spend at the hospital and I worry just a little bit less.

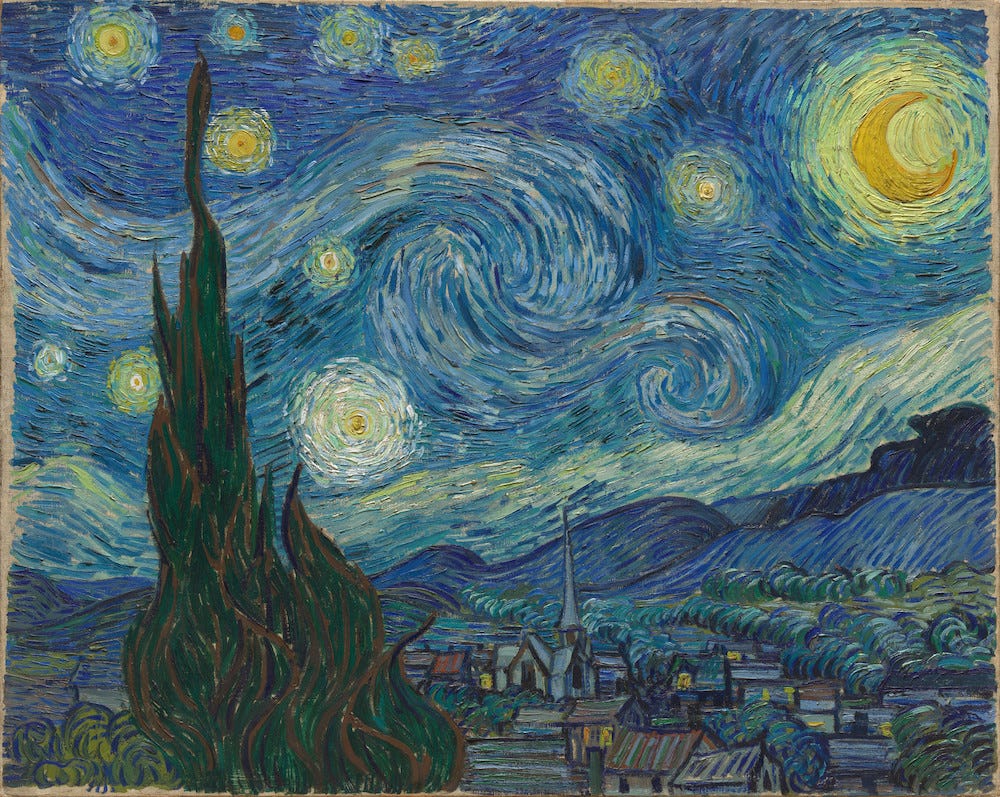

As for bad news, it’s relatively minor. Nuvia and I bought a 2,000-piece puzzle of Vincent Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” and it is kicking our collective asses. The thing has taken over our kitchen table and in almost two weeks time we’ve put the border together, a couple of the stars, and some shrubbery. I have a complicated relationship with Mr. Van Gogh, which I’ll get into if and when we finish the puzzle, but the odds of one of us sweeping the thing back into the box before then are 3 to 1.

You take your distractions where you can find them.

I’ve been able to write for the five weeks or so I’ve been staying at home, but not always, and not with the focus I would like. I’m doing a lot more journaling, baking, and—as of this weekend—art making.

I like having a project, preferably more than one project, and I’m fairly ambitious about what I take on and what I think I can handle. Last year, for instance, I bought The Sopranos Sessions by Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall. It’s got a short recap of every episode, a long interview with David Chase, plus additional reportage about the cast and crew. I thought, I’ll re-watch each episode of The Sopranos and follow along in the book.

Well, that didn’t happen. I got about a season into the project before I abandoned it for one deadline or another. Now that I’ve been staying at home, I’ve immersed myself in the world of North Jersey at the turn of the century and I just finished Season 3. It’s been immensely gratifying, like spending time with old friends (who happen to be sociopaths).

This is how my mind works. Oh, so and so has a new book/movie/album out? I think I’ll go back and re-read, re-watch, re-visit the whole catalog and then enjoy the new one. Well, more often then not, I never get to the enjoyment part because I’ve saddled myself with all that extra homework.

I’ve always been like this. When I was kid and got my first radio, I’d obsessively listen to the Billboard Top 40 and write down every song and artist in a notebook. I’d do this for a few weeks, hunched over my clock radio, and then abandon it.

Last year when I learned that Irish author Patrick McCabe had written a new book called The Big Yaroo, a sequel to his breakout book The Butcher Boy, I immediately wrote to the publisher, New Island Press, and requested a copy. Peter Murphy, writing for the Irish Times, perfectly captures The Butcher Boy’s significance:

“When Patrick McCabe’s third book, The Butcher Boy, was published, in 1992, its effect on Irish fiction was not unlike the impact The Sex Pistols’ Never Mind the Bollocks had on popular music. Though set in the early 1960s, the novel, like A Clockwork Orange before it, seemed closer to a proto- punk artefact than a literary phenomenon. Its publication represented a new year zero in Irish writing. Almost every subsequent small-town Hiberno coming-of-age novel has been branded by its influence.”

The Butcher Boy tells the story of Francie Brady, a charismatic, ebullient young man from a fictional Irish town near the border based on Clones, where McCabe grew up. Francie is in a tough spot. His mother is unstable, his father is a drunk, and Francie suffers from what could best be described as an overcrowded mind. He’s a boy with vast enthusiasm for the pop culture of the 1960s and runs around the countryside playing Cowboys and Indians with his best friend Joe, to whom he is devoted.

Problems begin when a nerdy schoolmate named Philip Nugent drives a wedge between the two boys, setting in motion a horrifying sequence of events that ends in a murder that feels both shocking and inevitable. But it’s Francie’s voice, a never-ending mix of boyish fantasy and family history that wins the reader over and exposes what it’s like to live in a small border down corrupted by religious fervor and worn down by oppression, paranoia, and squalor.

I don’t want to make generalizations about representations of rural Irish life in fiction. McCabe wasn’t the first to kick over a rock and expose the rot that had taken hold. Just last week I wrote about Flann O’Brien’s The Pour Mouth, which uses satire to do the very same thing in fictional Corkadoragha. For the most part, rural Irish novels set in the 1960s were full of parish priests, country doctors, and patient farmers with a gift for gab. Although Edna O’Brien dismantled these stereotypes with The Country Girls in 1960, the book was overshadowed by the outrage it caused. As Eimear McBride writes in the Irish Times:

“The moral hysteria that greeted the book ensured that both it and O’Brien have become era-defining symbols of the struggle for Irish women’s voices to be heard.”

Although The Butcher Boy is set during this period, it is informed by the horrors of the Troubles and the nihilism of the Cold War, which turns the furniture of the rural Irish novel into pieces for a macabre psychodrama.

The Butcher Boy was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, but the 1997 adaption by Neil Jordan brought McCabe’s vision to a wider audience. In fact, McCabe reputedly wrote several versions of the screenplay, some of which took liberties with his own story. Ultimately, Jordan decided to go with a draft that hewed close to the novel. (McCabe plays the town drunk, Jimmy the Skite.)

The film stars Stephen Rea as Francie’s father, Brendan Gleeson as a concerned priest, and Sinead O’Conner as the Virgin Mary, who appears in visions to Francie to admonish him for his behavior, “For fuck’s sake, Francie!”

But the star of the show is Eamonn Owen, who plays Francie, the troubled boy whose mind gushes like a spigot he can’t shut off. It’s one of the best performances I’ve ever seen by a child actor. Stephen Rea, who sulks around the set as Francie’s alcoholic father, also does spirited voiceovers from Frankie’s perspective many years later, which weirdly sets the stage for the sequel.

Before I sat down with The Big Yaroo, I re-watched The Butcher Boy again. I was delighted by how well it holds up and charmed anew by the troubled but sympathetic portrayal of Francie Brady.

In The Big Yaroo, Francie (now Frank) is well into his 60s and has spent most of the last five decades as an inmate of Fizzbag Mansions, a home for the criminally insane. On the outside, Frank is a docile man in medicated decline; but on the inside he’s still the the same irrepressible Francie Brady.

Thinking it might help Frank to have an outlet where he can express his thoughts, one of the priests at the asylum encourages him to write. Frank takes to the task with great gusto and decides to launch a news magazine called The Big Yaroo.

Frank adopts the pose of J. Jonah Jameson, Spider Man’s editor-in-chief at The Daily Bugle, as he goes about putting the paper together. Many of the stories concern “amazing facts,” some describe his boyhood adventures “in the wastes of time and space” with his old pal Joe, while other stories are profiles of his fellow inmates at Fizzbag Mansions, many of whom are in worse shape than Frank. How much worse is never quite clear. The Big Yaroo is a nesting doll of unreliable narrators that makes it all but impossible to distinguish fact from fantasy.

Frank is obsessed with Captain Troy Tempest, who pilots the vessel Stingray for the World Aquanaut Security Patrol in the year 2060. I thought this was another one of Frank’s inventions, but it’s not. Stingray was a British science fiction television series that featured marionettes.

Are Frank’s stories true? Is The Big Yaroo real? Is Frank going to make good on his plot to escape Fizzbag Mansions once and for all? These questions power the plot along to its surprising conclusion.

I want to go back to Murphy’s idea of “a new year zero.” The Butcher Boy was an event that changed the landscape for a certain nation of writers writing about a certain subject. If we look at the phrase “changed the landscape” in terms of American letters, I don’t think there are many events that qualify, and most of those are publishing events, i.e. a book that wins awards/gets made into a movie/makes boatloads of money because of x, y, and z. That’s not interesting to me.

I think the global pandemic qualifies as an event that has truly changed the landscape and ushered in a new year zero. It has already wrought a cascade of changes we’ll be dealing with for the rest of the decade, if not longer. It’s changing the way we think about everything from travel to public health, how we work to where our food comes from. This global re-set just might be the thing that gives this country the will to fix our broken healthcare system or make the kind of radical changes needed to save the planet.

It can also be the catalyst for personal change. The lapsed Catholic in me is still low-key obsessed with the idea of grace, a clean slate, a state from which all things are possible. I’m still hopeful enough to believe that each new earnest distraction represents an opportunity to re-set the clock.

Even a 2,000-piece puzzle of a night sky fogged with madness.

Bad Religion updates

I know many of you are bummed that Bad Religion had to cancel it’s spring tour, but you may get to hear a new recording of a Bad Religion song sooner rather than later. New Jersey’s Senses Fail is working on an album of cover songs and “We’re Only Gonna Die” is one of them. In fact, it’s already been recorded. Why should you care? Senses Fail guitarist Gavin Caswell is the band’s go-to guitar tech when Bad Religion is on the road, and he’s a super nice guy. The first time we met he was stringing one of Brian Baker’s guitars while the band rehearsed and he explained to me the whole mechanics of the process, all the way down to how guitar strings are made. I’ll post a link as soon as the song becomes available.

I can’t say too much about this at the moment, but it looks like there’s going to be a German version of Do What You Want. Why is this a big deal? Germany played (and continues to play) a huge role in the band’s global success. I’m not going to go into details because it’s an interesting chapter in the book, but this is exciting news.

Collector’s item alert! If you follow Bad Religion on Instagram, you may have seen a rectangular flexi disc spinning on a turntable. (A flexi is a record stamped on a flexible surface.) This one features an image of the cover of Do What You Want and when you put it on your turntable and drop the needle, a Bad Religion song plays. (I’ll give you three guesses as to which one and the first two don’t count.) The original plan was to give these flexis away during the spring tour. That obviously didn’t happen. The publisher is putting together a promotion for an extremely limited number of these items, and I’ll share the details as soon as they become available. Hint: when you pre-order the book, (which you can do save your receipt, and keep it handy.

How much art can you take?

I was finally able to sit and make some art last weekend and I’m really excited with the results.

A few weeks ago I bravely (foolishly?) volunteered to make some art for Hobart’s annual baseball edition. Jim Redmond’s poem “Baseball Dads All the Way Down” accompanied went live today by my linocut print. I had so much fun doodling and sketching and carving and printing this piece.

I also put what I hope is the finishing touches on the cover art for Our Love Cuts Deep, a short story that I’m making into a zine. If all goes as planned I’ll have the zine available soon. I haven’t been this excited about printmaking in a long, long time.

Be safe. Stay home. Keep well.

Keep at the puzzle!